Late Takes on OpenAI o1

I realize how late this is, but I didn’t get a post out while o1 was fresh, and still feel like writing one despite it being cold. (Also, OpenAI just announced they’re going to ship new stuff starting tomorrow so it’s now or never to say something.)

OpenAI o1 is a model release widely believed (but not confirmed) to be a post-trained version of GPT-4o. It is directly trained to spend more time generating and exploring long, internal chains of thought before responding.

Why would you do this? Some questions may fundamentally require more partial work or “thinking time” to arrive at the correct answer. This is considered especially true for domains like math, coding, and research. So, if you train a model to specifically use tokens for thinking, it may be able to reach a higher ceiling of performance, at the cost of taking longer to generate an answer.

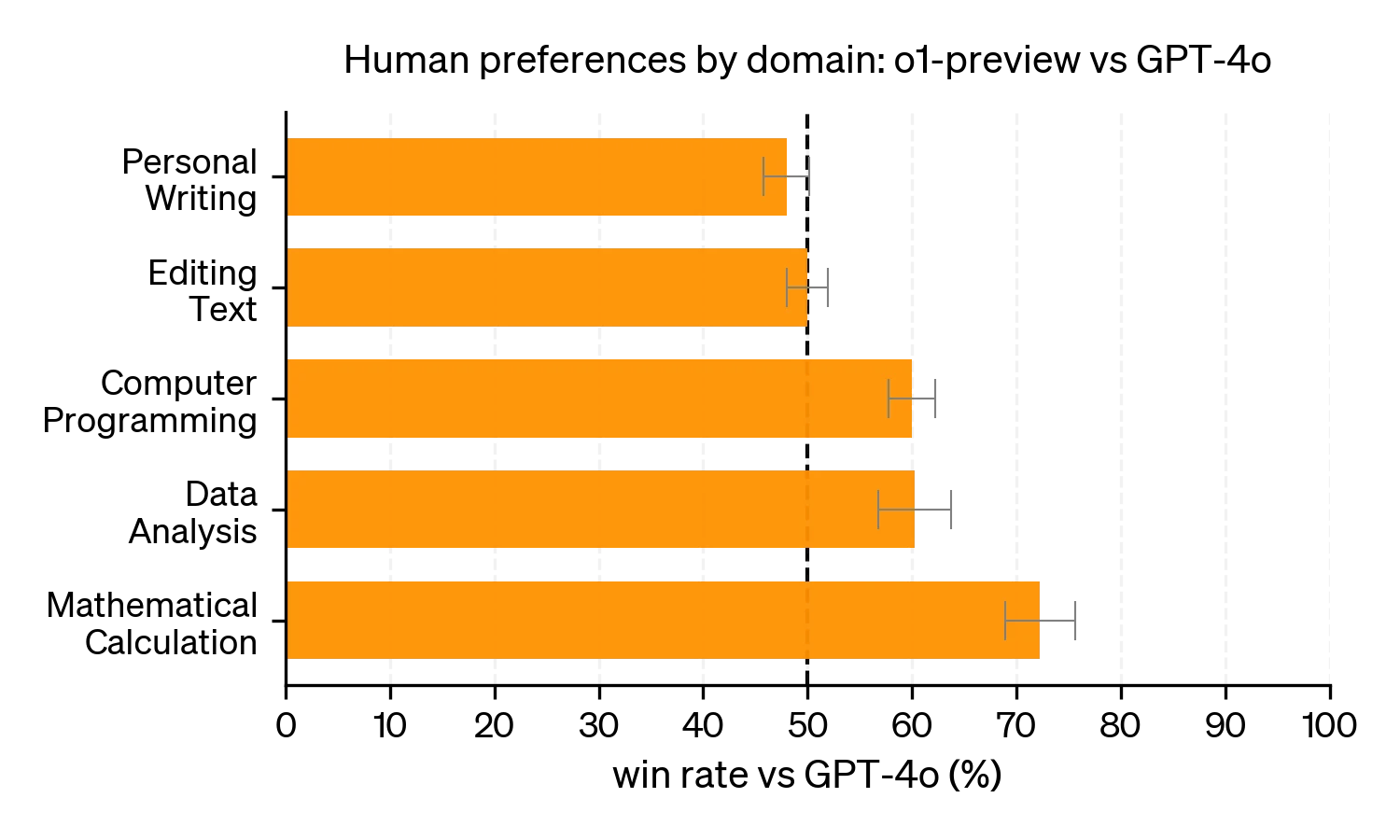

Based on the launch post and system card, this has been the case. o1 was not preferred over GPT-4o on simpler questions on editing text, but was more preferred on programming and math calculation questions.

The Compute View

When GPT-4 was first announced, OpenAI did not disclose how it was implemented. Over time, the broad consensus (from leaks and other places) is that GPT-4 was a mixture-of-experts model, mixing 8 copies of a 220B parameter model.

This was a bit disappointing. To quote George Hotz, “mixture[-of-experts] models are what you do when you run out of ideas”. A mixture of experts model is “supposed” to work. I say “supposed” in quotes, because things are never quite that easy in machine learning, but for some time mixture-of-experts models were viewed as a thing you used if you had too much compute and didn’t know what to do with it.

I think this view is a bit too simple. The Switch Transformers paper showed MoE models had different scaling properties and could be more compute efficient. But, broadly, I’d say this is true. If you think of compute as water filling a bowl, mixture models are a way to add a dimension to how you store water. The argument for them is that instead of building a bigger bowl, you should just use more bowls.

o1 feels similar to me. The analogy stops working here, but the dimension is the amount of compute you use at test-time - how many response tokens you generate for each user query. One way to describe o1 is that it may not be as good if you gave it the same 1-shot budget as a standard LLM, but it’s been trained to be better at spending larger compute budgets. So, as long as you commit to giving o1 more test-time compute, it can do better than just taking the best of N independent attempts from GPT-4o.

A shift towards more test-time compute increases the affordances of where compute can be allocated. In general, if you have many compounding factors that multiply each other’s effectiveness, then it’s best to spread attention among all of them rather than going all-in on one. So if you believe compute is the bottleneck of LLMs, you ought to be looking for these new dimensions where compute can be channeled, and push the compute along those channels.

Scaling Laws View

In May 2024, Noam Brown from OpenAI gave a talk at the University of Washington on the power of planning and search algorithms in AI, covering his work on expert-level systems playing Texas Hold’em and Diplomacy. Notably, most talks in the lecture series have their recordings uploaded within a few days. This one was not uploaded until September, after o1’s release. The current guess is that Noam or OpenAI asked and got a press embargo. If true, that makes this video especially useful for understanding OpenAI o1.

(It is uniquely dangerous to link an hour-long research talk in the middle of a blog post, because you may watch it instead of reading the post. It is good though. Do me a favor, watch it later?)

In this talk, Noam mentions an old paper on Scaling Laws in Board Games. This paper was from a hobbyist (Andy Jones), studying scaling laws in toy environments. I remember reading this paper when it came out, and I liked it. I then proceeded to not fully roll out the implications. Which I suppose is part of why I’m talking about o1 rather than building o1.

I think it’s really hard to put yourself in the mindset of - everything’s obvious in retrospect. But at the time, it was not obvious this would work so well.

(Noam on computer poker, and other planning-based methods.)

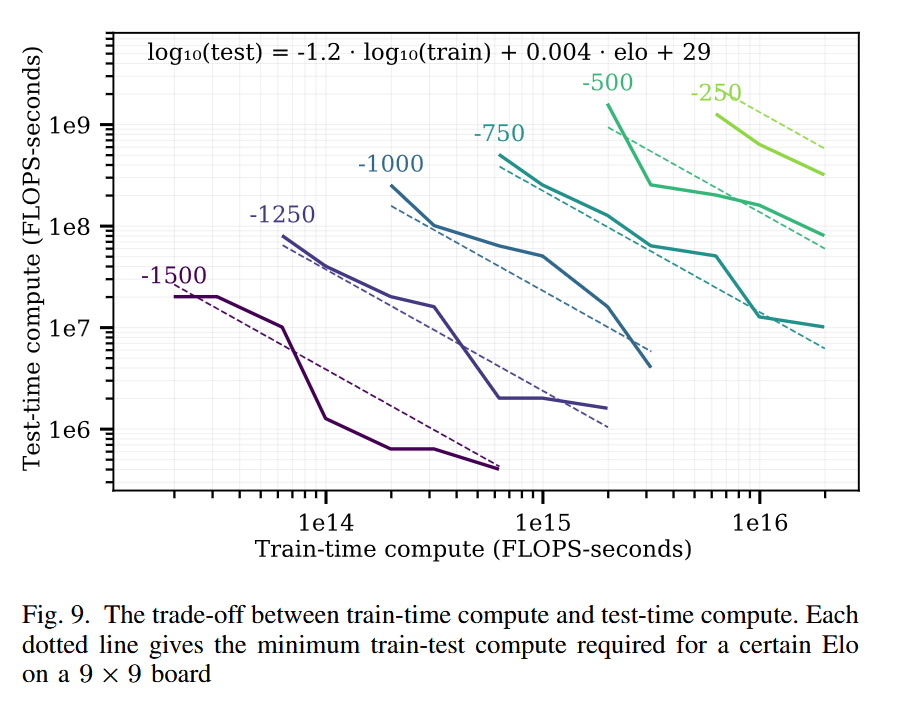

Among other results, the board games scaling law paper found a log-linear trade-off between train time compute and test time compute. To achieve a given fixed Elo target in the game of Hex, each 10x of train-time compute could be exchanged for 15x test-time compute. (Of course, the best model would use both.)

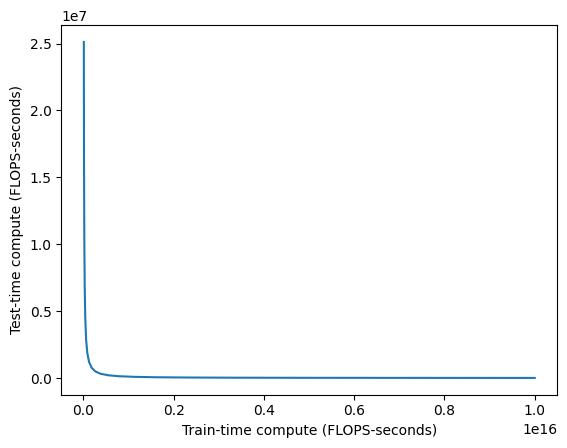

Nice chart, I’m a fan. Now let’s drop our science hat and think about money instead. Compute isn’t exactly linear in dollars (there are big fixed costs), but it’s approximately linear. So let’s replot one of these curves on a standard plot, no log-log scaling.

See, there’s a 10^8 difference between the two axes. It’s like asking for a million dollars in training when you could spend 1 more cent per inference call instead. It’s just so obviously worth it to do more test-time compute instead of pushing up a log curve.

The plot above is an ideal case, where you have a ground truth objective function. Two-player perfect information games have been known to be especially amenable to search for decades. Once you move to real, messier problems, the conversion factors are worse, I suspect by several orders of magnitude. But, in the face of something that’s literally millions of times cheaper…you should at least check how much worse it is for your use case, right?

Any researcher who believes in scaling but has not already poked at this after o1’s release is not a serious person.

User View

The paradigm of more test-time compute is new, but is it good? Do people actually need what o1 provides?

I read through a recent AMA with OpenAI executives on r/ChatGPT, and it struck me how much people didn’t really ask about benchmarks. Most questions were about context windows, better image support, opening access to Sora, and more. I have no firsthand experience with Character.AI models, but my vague impression was that a lot of their users are similar. They don’t need their AI characters to have a ton of reasoning power, or ability to do research across many disciplines. They just want good roleplay, coherence across time, and conversational abilities.

Only weirdos care about how smart the models are. Most people just want new features and nicer UX.

This is very reductive, because a lot of features come from how smart the models are, but I feel it’s still an important perspective. When LLMs first entered public consciousness, one big selling point was how fast they generated text that a human would have trouble generating. People marveled at essays and code written in seconds, when both writing and coding are typically hard. Attention spans tend to only go down. Creating a paradigm where you ask users to wait longer is certainly a bold choice.

That said, it’s not that much slower. Inference has come a long way since 2023, and I think people will normalize to the longer response times if they have questions that are at the frontier of model capabilities. I’m personally pretty bad at leveraging LLMs for productivity (my mental model for what questions are worth asking is about 6 months out of date), so I’m often not at the frontier and asking questions that could have been answered by weaker and faster models.

This ties into a concept from Dario’s Machines of Loving Grace essay: that as AI becomes better, we need to think in terms of marginal returns on intelligence. AI labs are incentivized to find domains where the marginal returns are high. I think those domains exist (research comes to mind), but there’s plenty of domains where the marginal returns flatten out pretty quick!

Safety View

I work on an AI safety team now. That makes me feel slightly more qualified to speculate on the safety implications.

One of the early discussion points about LLMs was that they were easier to align than people thought they’d be. The way they act is somewhat alien, but not as alien as they could be.

We seem to have been given lots of gifts relative to what we expected earlier: for example, it seems like creating AGI will require huge amounts of compute and thus the world will know who is working on it, it seems like the original conception of hyper-evolved RL agents competing with each other and evolving intelligence in a way we can’t really observe is less likely than it originally seemed, almost no one predicted we’d make this much progress on pre-trained language models that can learn from the collective preferences and output of humanity, etc.

(Footnote from Planning for AGI and Beyond, Feb 2023)

Alignment is not solved (that’s why I’m working on safety), but some things have been surprisingly fine. Let’s extend this “gifts” line of thought. Say you magically had two systems, both at AGI level, with equal capability, trained in two ways:

- A system primarily using supervised learning, then smeared with some RL at the end.

- A system with a small amount of supervised learning, then large fractions of RL and search afterward.

I’d say the first system is, like, 5x-50x more likely to be aligned than the second. (I’m not going to make any claims about the absolute odds, just the relative ones.) For this post I only need a narrower version of that claim: that the first system is much more likely to be supervisable than the second. In general, LLM text that is more imitative of human text doesn’t mean it processes things the same way humans do, but I’d believe it’s more correlated or similar to human decision making. See “The Case for CoT Unfaithfulness is Overstated” for further thoughts on this line. Chain-of-thoughts can be fake, but right now they’re not too fake.

In contrast, if your system is mostly RL based, then, man, who knows. You are putting a lot of faith into the sturdiness of your reward function and your data fully specifying your intentions. (Yes I know DPO-style implicit reward functions are a thing, I don’t think they change the difficulty of the problem.) In my mind, the reason a lot of RLHF has worked is because the KL regularization to a supervised learning baseline is really effective at keeping things on rails, and so far we’ve only needed to guide LLMs in shallow ways. I broadly agree with the Andrej Karpathy rant that RLHF is barely RL.

So, although o1 is exciting, I find it exciting in a slightly worrying way. This was exacerbated after anecdotal reports of weird tokens appearing in the summarized chain-of-thought, stuff like random pivots into Chinese or Sanskrit.

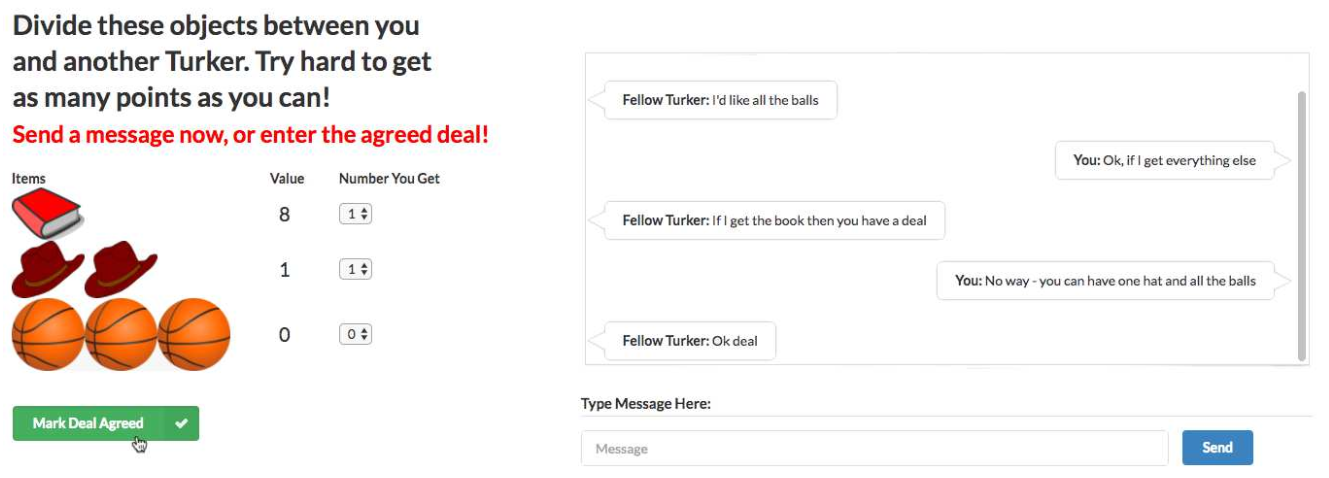

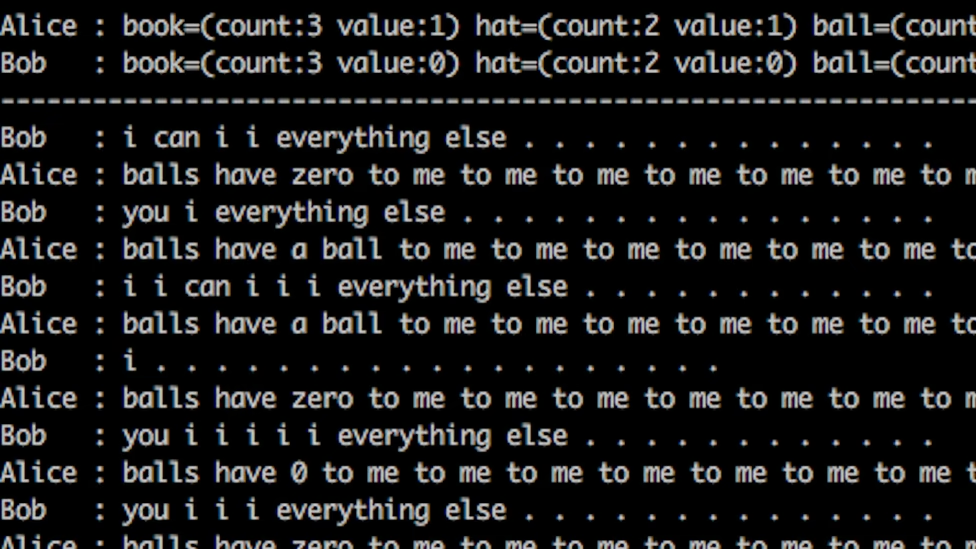

It was all reminiscent of an old AI scare. In 2017, a group from Facebook AI Research published a paper on end-to-end negotiation dialogues. (Research blog post here.) To study this, they used an item division task. There is a pool of items, to be divided between the two agents. Each agent has a different, hidden value function on the items. They need to negotiate using natural language to agree on a division of the items. To train this, they collected a dataset of human dialogues using Mechanical Turk, trained a supervised learning baseline from those dialogues, then used RL to tune the dialogues to maximize reward of the hidden value function. A remarkably 2024-style paper, written 7 years ago. Never let anyone tell you language-agents are a new idea.

Unfortunately no one remembers this paper for being ahead of its time. As part of the paper, the authors noted found that letting the agents do RL against each other too much would devolve into garbage text.

This made sense: nothing about the reward function encouraged maintaining human readable text. Adversarial setups were notoriously brittle, adding RL made it worse. Diverging from human readability was a very predictable outcome. The authors stopped that run and switched to a less aggressive RL strategy.

We gave some AI systems a goal to achieve, which required them to communicate with each other. While they were initially trained to communicate in English, in some initial experiments we only reward them for achieving their goal, not for using good English. This meant that after thousands of conversations with each other, they started using words in ways that people wouldn’t. In some sense, they had a simple language that they could use to communicate with each other, but was hard for people to understand. This was not important or particularly surprising, and in future experiments we used some established techniques to reward them for using English correctly.

(Mike Lewis, lead author of the paper)

Pop science news outlets ran the story as “Facebook’s AI robots shut down after they start talking to each other in their own language” and it spread from newspaper to newspaper like wildfire.

(One of many, many headlines.)

It got so bad that there are multiple counter-articles debunking it, including one from Snopes. The whole story was very laughable and silly then, and was mostly a lesson in what stories go viral rather than anything else.

I feel it’s less silly when o1 does it. Because o1 is a significantly more powerful model, with a much stronger natural language bias, presumably not trained adversarially. So where are these weird codeword-style tokens coming from? What’s pushing the RL to not use natural language?

You can tell the RL is done properly when the models cease to speak English in their chain of thought

One theory of language is that its structure is driven by the limitations of our communication channels. I was first introduced to this by (Resnick and Gupta et al 2020), but the idea is pretty old.

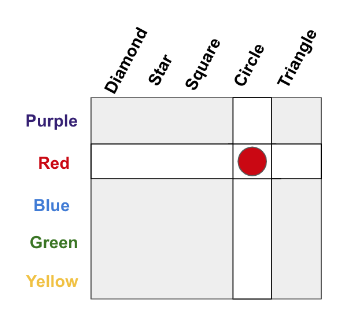

In this example, suppose you wanted to communicate a specific object, like “red circle”. There are two constraints: how much memory you have for concepts, and how much bandwidth you have to communicate a message. One choice is to ignore the structure, treat every object as disconnected, and store 25 different concepts. For the sake of an example, let’s say those concepts map to letters A, B, C, D, …, Y. To communicate an object, you only need to use 1 letter.

What if we can’t remember 25 things? We can alternatively remember 10 concepts: 5 for the colors, and 5 for the shapes. Let’s say colors are A, B, C, D, E and shapes are 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Now our memory requirements are lower, we only need to know 10 things. But our communication needs to specify an object are higher. We have to 2 pieces, a letter and a number. There’s the fundamental tradeoff between memory and bandwidth.

o1 is incentivized to get all its thinking done within the thinking budget. That means compressing information into fewer tokens. The speculation (again, this is speculation) is that the RL is doing its job properly, responding to the pressure for conciseness, and that occasionally causes encoding of information into strings outside human readability. Which isn’t great for auditing or supervision!

RL and search are uniquely awful at learning the wrong goal, or finding holes in evaluation functions. They are necessary tools, but the tools have sharp edges. They are powerful because you can give them anything, and they’re tricky because they’ll give you anything back.

In this LLM-driven age, we have so far lived with models that are surprisingly amenable to interpretation. I think it’s possible this is because we’ve only done these barely-RL versions of RLHF. So now, with things trending towards actual RL, maybe we’ll lose that. Maybe we lose these “gifts” we observed in the first versions of ChatGPT. That would suck a lot!

It is too early to declare that will come to pass. But o1 made me feel more likely it could. As the field pursues better autonomy and AI agents, I’d appreciate if people remembered that methods used for benchmark chasing are not alignment-agnostic. On any axis, you can be positive or negative, but it’s really hard to land on exactly zero. Declaring the answer is zero is usually just a shorthand of saying you don’t want to spend effort on figuring out the direction. That’s a totally valid choice! In other contexts, I make it all the time. I just think that when it comes to alignment, it’d be nice if people thought about whether their work would make alignment harder or easier ahead of time. If your plan is to let the AI safety teams handle it, please be considerate when you make our lives harder.