Using AI to Get the Neopets Destruct-o-Match Avatar

I have blogged about Neopets before, but a quick refresher. Neopets is a web game from the early 2000s, which recently celebrated its 25th anniversary and maintains a small audience of adult millennials. It’s a bit tricky to sum up the appeal of Neopets, but I like the combination of Web 1.0 nostalgia and long-running progression systems. There are many intersecting achievement tracks you can go for, some of which are exceedingly hard to complete. Among them are books, pet training, stamp collecting, gourmet foods, Kadoaties, and more.

The one I’ve been chasing the past few years is avatars. Neopets has an onsite forum called the Neoboards. This forum is heavily moderated, so you can only use avatars that have been created by TNT. Some are available to everyone, but most have unlock requirements. The number of avatars someone has is a quantification of how much investment they’ve put into Neopets. In my opinion, avatars are the best achievement track to chase, because their unlocks cover the widest cross-section of the site. To get all the avatars, you’ll need to do site events, collect stamps, play games, do dailies, and more. There’s a reason they get listed first in your profile summary!

The avatar I’m using right now literally took me 5 years to unlock. I’m very glad I have it.

Avatars start easy, but can become fiendishly difficult. To give a sense of how far they can go, let me quote the post I wrote on the Neopets economy.

The Hidden Tower Grimoires are books, and unlike the other Hidden Tower items, they’re entirely untradable. You can only buy them from the Hidden Tower, with the most expensive one costing 10,000,000 NP. Each book grants an avatar when read, disappearing on use.

Remember the story of the I Am Rich iOS app, that cost $1000, and did literally nothing? Buying the most expensive Grimoire for the avatar is just pure conspicuous consumption. […] They target the top 1% by creating a new status symbol.

I don’t consider myself the Neopets top 1%, but since writing that post, I’ve bought all 3 Hidden Tower books just to get the avatars…so yeah, they got me.

Avatars can be divided by category, and one big category is Flash games. These avatars all have the same format: “get at least X points in this game.” Most of the game thresholds are evil, since they were set to be a challenge based on high-score tables from the height of Neopets’ popularity. Getting an avatar score usually requires a mix of mastery and luck.

Of these avatars, one I’ve eyed for a long time is Destruct-o-Match.

Destruct-o-Match is a block clearing game that I genuinely find fun. Given a starting board, you can clear any group of 2 or more connected blocks of the same color. Each time you do so, every other block falls according to gravity. Your goal is to clear as many blocks as possible. You earn more points for clearing large groups at once, and having fewer blocks leftover when you run out of moves. The game is made of 10 levels, starting with a 12 x 14 grid of 4 colors and ending with a 16 x 18 grid of 9 colors.

My best score as a kid was 1198 points. The avatar score is 2500. For context, top humans can reach around 2900 to 3000 points on a good run.

Part of the reason this has always been a white whale for me is that it’s almost entirely deterministic from the start state. You could, in theory, figure out the optimal sequence of moves for each level to maximize your score. Actually doing so would take forever, but you could. There’s RNG, but there’s skill too.

Destruct-o-Match can be viewed as a turn based game, where your moves are deciding what boulders to remove. That puts it in the camp of games like Chess and Go, where AI developers have created bots that play at a superhuman level. If AI can be superhuman at Go, surely AI can be slightly-worse-than-experts at Destruct-o-Match if we try?

This is the story of me trying.

Step 0: Is Making a Destruct-o-Match AI Against Neopets Rules?

There’s a gray area for what tools are allowed on Neopets. In general, any bot or browser extension that does game actions or browser requests for you is 100% cheating. Things that are quality-of-life improvements like rearranging the site layout are fine. Anything in-between depends on if it crosses the line from quality-of-life improvement to excessive game assistance, but the line is hard to define.

I believe the precedent is in favor of a Destruct-o-Match AI being okay. Solvers exist for many existing Flash games, such as an anagram solver for Castle of Eliv Thade, Sudoku solvers for Roodoku, and a Mysterious Negg Cave Puzzle Solver for the Negg Cave daily puzzle. These all cross the line from game walkthrough to computer assisted game help, and are all uncontroversial. As long as I’m the one inputting moves the Destruct-o-Match AI recommends, I should be okay.

Step 1: Rules Engine

Like most AI applications, the AI is the easy part, and engineering everything around it is the hard part. To write a game AI, we first need to implement the rules of the game in code. We’ll be implementing the HTML5 version of the game, since it has a few changes from the Flash version that make it much easier to get a high score. The most important one is that you can earn points in Zen Mode, which removes the point thresholds that can cause you to fail levels and Game Over early in the Flash version.

To represent the game, we’ll view it as a Markov decision process (MDP), since that’s the standard formulation people use in the literature. A Markov decision process is made of 4 components:

- The state space, covering all possible states of the game.

- The action space, covering all possible actions from a given state.

- The transition dynamics, describing what next state you’ll reach after doing an action.

- The reward, how much we get for doing that action. We are trying to maximize the total reward over all timesteps.

Translating Destruct-o-Match in these terms,

- The state space is the shape of the grid and the color of each block in that grid.

- The possible actions are the different groups of matching color.

- The transition dynamics are the application of gravity after a group is removed.

- The reward is the number of points the removed group is worth, and the end score bonus if we’ve run out of moves.

The reward is the easiest to implement, following this scoring table.

| Boulders Cleared | Points per Boulder | Bonus Points |

|---|---|---|

| 2-4 | 1 | - |

| 5-6 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 1 | 2 |

| 8-9 | 1 | 3 |

| 10 | 1 | 4 |

| 11 | 1 | 6 |

| 12-13 | 1 | 7 |

| 14 | 1 | 8 |

| 15 | 1 | 9 |

| 16+ | 2 | - |

The end level bonus is 100 points, minus 10 points for every leftover boulder.

| Boulders Remaining | Bonus Points |

|---|---|

| 0 | 100 |

| 1 | 90 |

| 2 | 80 |

| 3 | 70 |

| 4 | 60 |

| 5 | 50 |

| 6 | 40 |

| 7 | 30 |

| 8 | 20 |

| 9 | 10 |

| 10+ | 0 |

Gravity is also not too hard to implement. The most complicated and expensive logic is on identifying the possible actions. We can repeatedly apply the flood-fill algorithm to find groups of the same color, continuing until all boulders are assigned to some group. The actions are then the set of groups with at least 2 boulders. This runs in time proportional to the size of the board. However, it’s not quite that simple, thanks to one important part of Destruct-o-Match: powerups.

Powerups

Powerups are very important to scoring in Destruct-o-Match, so we need to model them accurately. Going through them in order:

|

The Timer Boulder counts down from 15 seconds, and becomes unclearable if not removed before then. |

|

The Fill Boulder will add an extra line of blocks on top when cleared. |

|

The Explode Boulder is its own color and is always a valid move. When clicked, it and all adjacent boulders (including diagonals) are removed, scoring no points. |

|

The Overkill Boulder destroys all boulders of matching color when cleared, but you only get points for the group containing the Overkill. |

|

The Multiplier Boulder multiples the score of the group it's in by 3x. |

|

The Morph Boulder cycles between boulder colors every few seconds. |

|

The Wild Boulder matches any color, meaning it can be part of multiple valid moves. |

|

The Shuffle Boulder gives a one-shot use of shuffling boulder colors randomly. The grid shape will stay fixed. You can bank 1 shuffle use at a time, and it carries across levels. |

|

The Undo Boulder gives a one-shot use of undoing your last move, as long as it did not involve a power-up. Similar to shuffles, you can bank 1 use at a time and it carries across levels. In the HTML5 version, you keep all points from the undone move. |

We can keep the game simpler by ignoring the Shuffle and Undo powerups. These both assist in earning points, but they introduce problems. Shuffle would require implementing randomness. This would be harder for the AI to handle, because we’d have to average over the many possible future states to estimate the value of each action. It’s possible, just expensive. Meanwhile, Undos require carrying around history in the state, which I just don’t want to deal with. So, I’ll have my rules engine pretend these powerups don’t exist. This will give up some points, but remember, we’re not targeting perfect play. We just want “good enough” play to hit the avatar score of 2500. Introducing slack is okay if we make up for it later. (I can always use the Shuffle or Undo myself if I spot a good opportunity to do so later.)

Along similar lines, I will ignore the Fill powerup because it adds randomness on what blocks get added, and will ignore the Timer powerup because I want to treat the game as a turn-based game. These are harder to ignore. My plan is to commit to clearing Timer boulders and Fill boulders as soon as I start the level. Then I’ll transcribe the resulting grid into the AI and let it take over from there.

This leaves Explode, Overkill, Multiplier, Morph, and Wild. Morph can be treated as identical to Wild, since we can wait for the Morph boulder to become whatever color we want it to be. The complexity these powers add is that after identifying a connected group, we may remove boulders outside that group. A group of blue boulders with an Overkill needs to remove every other blue boulder. So, for every group identified via flood-fill, we note any powerups contained in that group, then iterate over them to define an “also-removed” set for that action. (There are a lot of minor, uninteresting details here, my favorite of which was that Wild Boulders are not the same color as Explode Boulders and Explode Boulders are not the same color as themselves.) But with those details handled, we’re done with the rules engine!

Well, almost done.

Step 2: Initial State

Although I tried to remove all randomness, one source of randomness I can’t ignore is how powerups are initially distributed.

Of the powerups, the Multiplier Boulder is clearly very valuable. Multiplying score by 3x can be worth a lot, and avatar runs are often decided by how many Multipliers you see that run. So for my AI to be useful, I need to know how often each powerup appears.

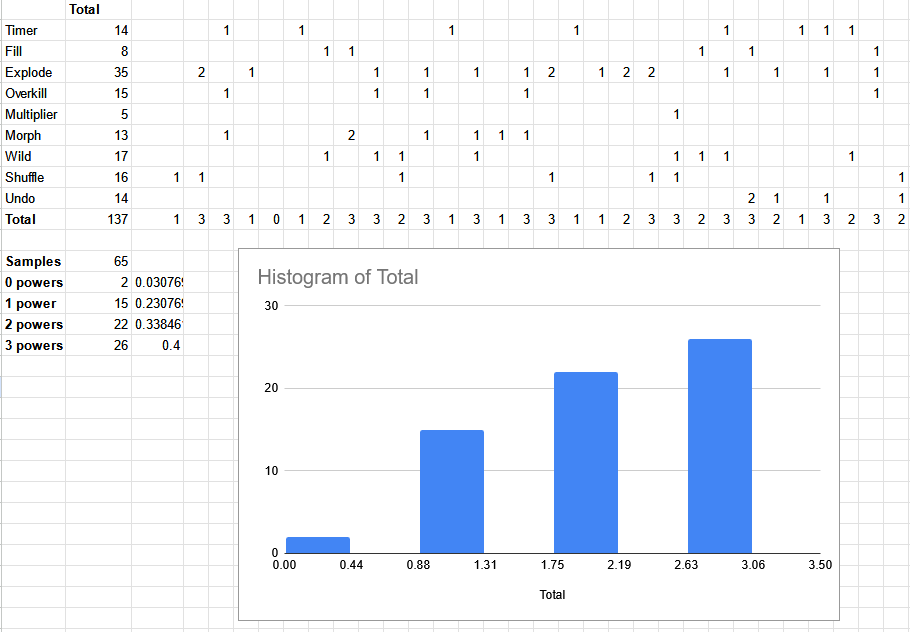

I couldn’t find any information about this on the fan sites, so I did what any reasonable person would do and created a spreadsheet to figure it out for myself.

I played 65 levels of Destruct-o-Match, tracking data for each one. Based on this data, I believe Destruct-o-Match first randomly picks a number from 0-3 for how many powerups will be on the board. If powerups were randomly selected per block, I would have seen more than 3 powerups at some point. I observed 0 powerups 3% of the time, 1 powerup 23% of the time, 2 powerups 34% of the time, and 3 powerups 40% of the time. For reverse engineering, I’m applying “programmer’s bias” - someone made this game, and it’s more likely they picked round, nice numbers. I decided to round to multiples of 5, giving 0 = 5%, 1 = 20%, 2 = 35%, 3 = 40% for powerup counts.

Looking at the powerup frequency, Explode clearly appears the most and Multiplier appears the least. Again applying some nice number bias, I assume that Explodes are 2x more likely than a typical powerup, Fills are 2/3rd as likely, and Multipliers are 1/3rd as likely, since this matches the data pretty well.

An aside here: in testing on the Flash version, I’ve seen more than 3 powerups appear, so the algorithm used there differs in some way.

Step 3: Sanity Check

Before going any further down the rabbit hole, let’s check how much impact skill has on Destruct-o-Match scores. If the scores are mostly driven by RNG, I should go play more games instead of developing the AI.

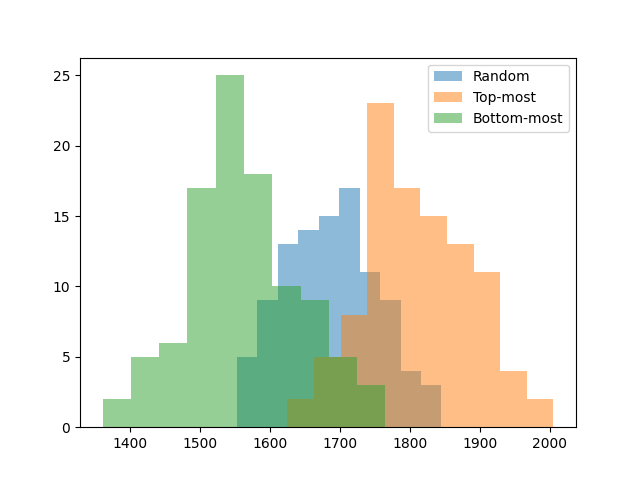

I implemented 3 basic strategies:

- Random: Removes a random group.

- Top-Down: Removes the top-most group.

- Bottom-Up: Removes the bottom-most group.

Random is a simple baseline that maps to a human player spamming clicks without thinking. (I have done this many, many times when I just want a game to be over.) Top-down and bottom-up are two suggested strategies from the JellyNeo fan page. Top-down won’t mess up existing groups but makes it harder to create new groups, since fewer blocks change location when falling. Bottom-up can create groups by causing more blocks to fall, but it can also break apart existing larger groups, which hurts bonus points.

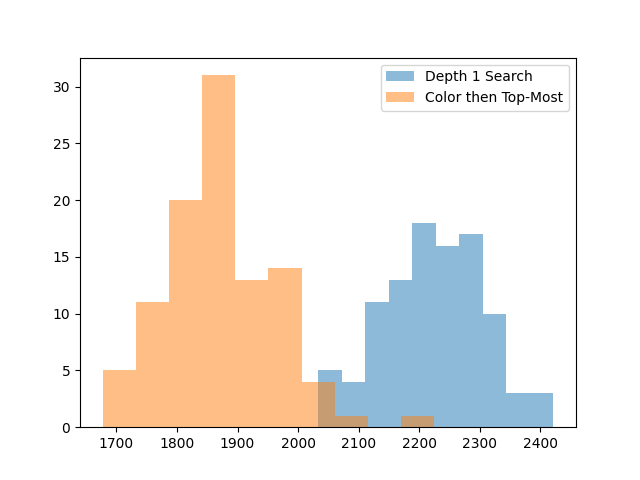

For each strategy, I simulated 100 random games and plotted the distribution of scores.

The good news is that strategy makes a significant difference. Even a simple top-most strategy is 100 points better than random. This also lets us know that the bottom-up strategy sucks. Which makes sense: bottom-up strategies introduce chaos, it’s hard to make large groups of the same color in chaos, and we want large groups for the bonus points. For human play, this suggests it’s better to remove groups near the top unless we have a reason not to.

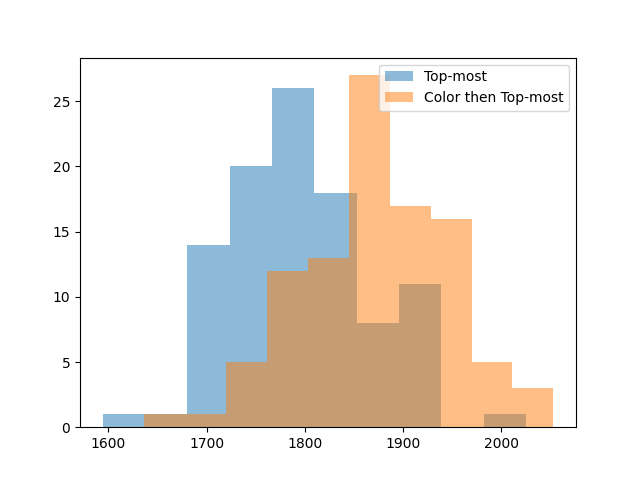

One last recommended human strategy is to remove blocks in order of color. The idea is that if you leave fewer colors on the board, the remaining groups will connect into large groups more often, giving you more bonus points. We can try this strategy too, removing groups in color order, tiebreaking with the top-down heuristic that did well earlier.

Removing in color order gives another 100 points on average. We can try one more idea: if bottom-up is bad because it breaks apart large groups, maybe it’d be good to remove large groups first, to lock in our gains. Let’s remove groups first in order of color, then in order of size, then in order of which is on top.

This doesn’t seem to improve things, so let’s not use it.

These baselines are all quite far from the avatar score of 2500. Even the luckiest game out of 100 attempts only gets to 2100 points. It is now (finally) time to implement the AI.

Step 4: The AI

To truly max the AI’s score, it would be best to follow the example of AlphaZero or MuZero. Those methods work by running a very large number of simulated games with MCTS, training a neural net to predict the value of boards from billions of games of data, and using that neural net to train itself with billions more games.

I don’t want to invest that much compute or time, so instead we’re going to use something closer to the first chess AIs: search with a handcoded value function. The value of a state \(s\) is usually denoted as \(V(s)\), and is the estimated total reward if we play the game to completion starting from state \(s\). If we have a value function \(V(s)\), then we can find the best action by computing what’s known as the Q-value. The Q-value \(Q(s,a)\) is the total reward we’ll achieve if we start in state \(s\) and perform action \(a\), and can be defined as.

\[Q(s,a) = reward(a) + Value(\text{next state}) = r + V(s')\]Here \(s'\) is the common notation for “next state”. The action \(a\) with largest Q-value is the action the AI believes is best.

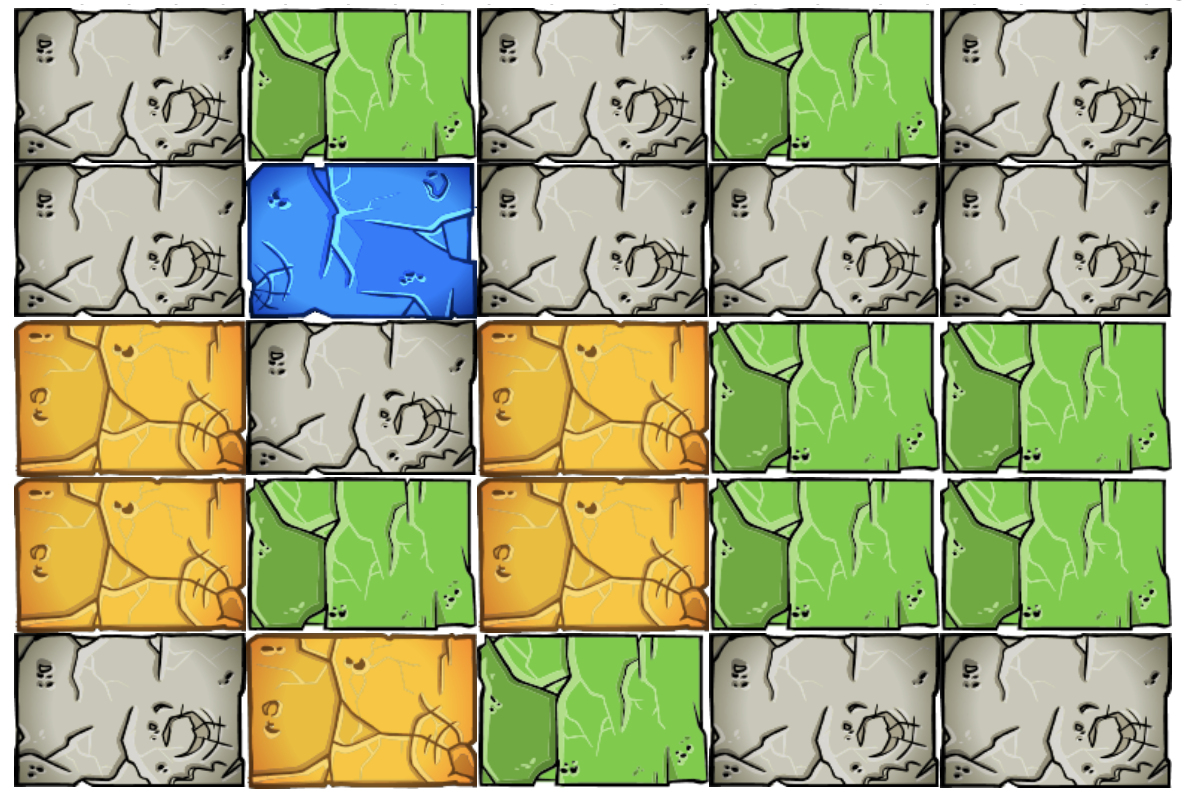

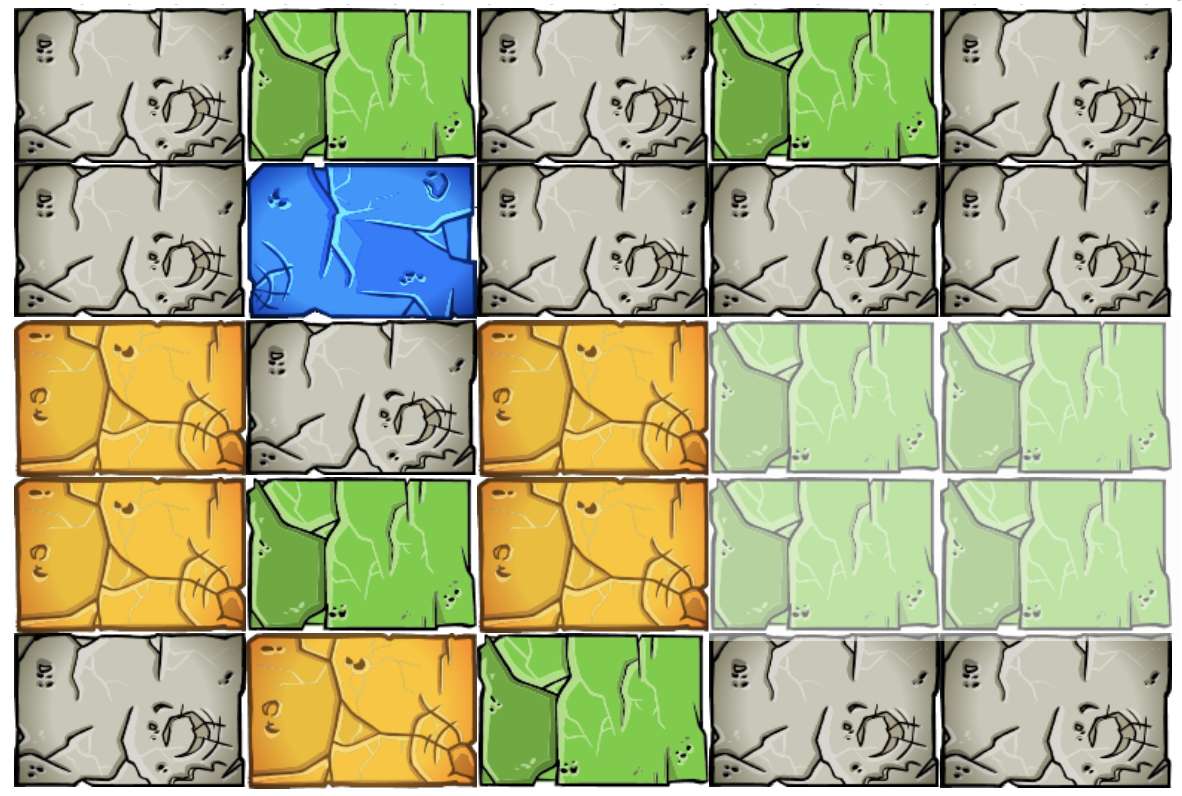

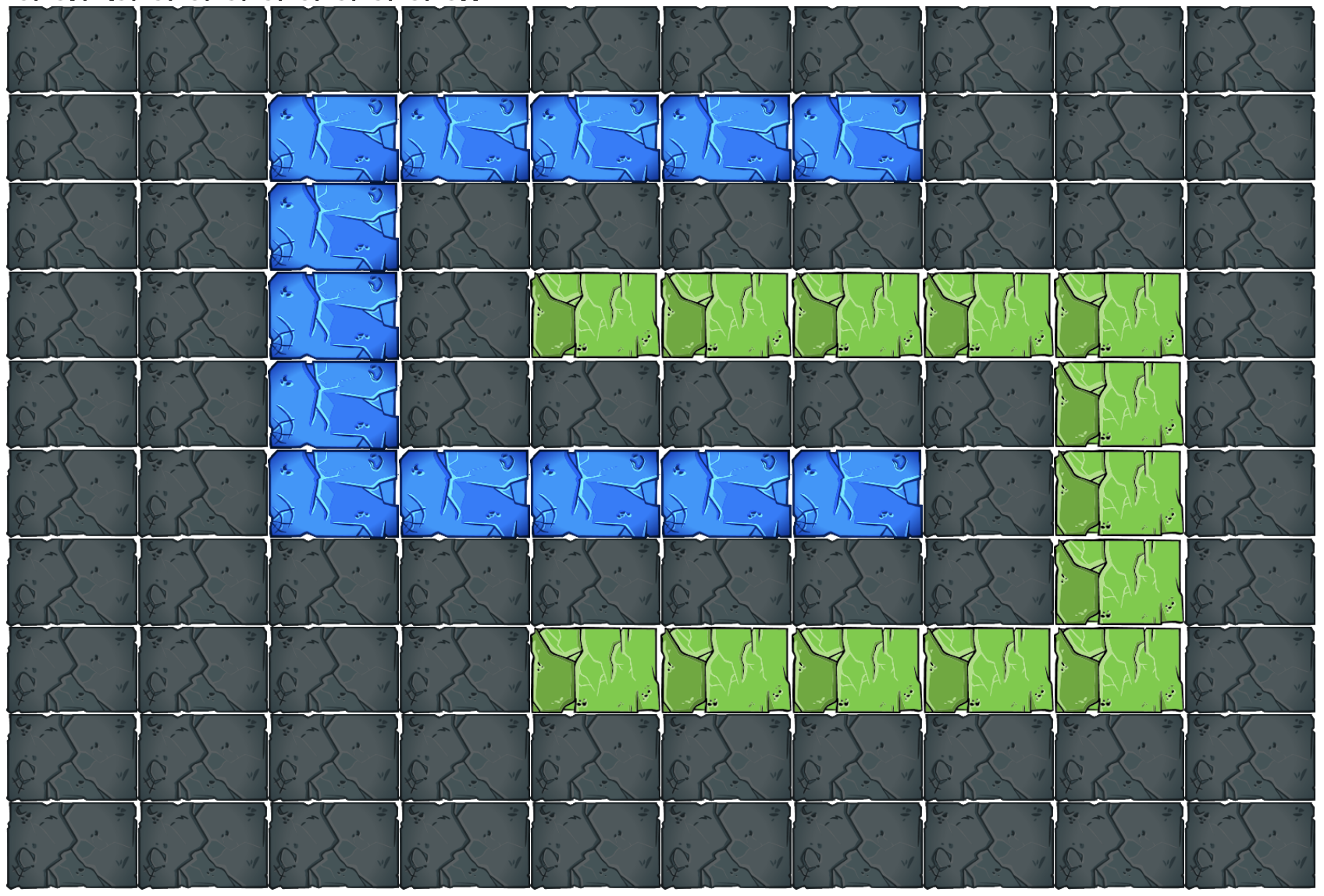

So how do we estimate the value? We can conservatively estimate a board’s value as the sum of points we’d get from every group that exists within it, plus the end-level bonus for every boulder that isn’t in one of those groups. This corresponds to scoring every existing group and assuming no new groups will be formed if all existing groups are removed. Doing so should be possible on most boards, if we order the groups such that a group is removed only after every group above it has been removed. Unfortunately, there are some edge cases where it isn’t possible, such as this double-C example, where groups depend on each other in a cycle.

In this example, we cannot earn full points for both the blue group and green group, because removing either will break apart the other.

We could determine if it’s possible to score every group by running a topological sort algorithm, but for our purposes we only need the value function to be an approximation, and we want the value function to be fast. So, I decided to just ignore these edge cases, for the sake of speed.

We can reuse the logic we used to find every possible action to find all groups in the grid. This gives a value estimate of

\[V(s) = \sum_{a} reward(a)\]Here is our new method for choosing actions.

- From the current state \(s\), compute every possible action \(a\).

- For each action \(a\), find the next state \(s'\) then compute Q-value \(Q(s,a) = r + V(s')\).

- Pick the action with best Q-value.

- Break ties with the color then top-most heuristic that did best earlier.

Even though this only looks 1 move ahead, it’s quite effective. By a lot.

This is enough to give a 400 point boost on its own. This gain was big enough that I decided to try playing a game with this AI, and I actually got pretty close to winning on my first try, with 2433 points.

The reason I got so many points compared to the distribution above is a combination of using Shuffles for points and beneficial bugs. I don’t know how, but I got a lot more points from the end-level bonuses in levels 3 and 4 than I was supposed to. I noticed that levels 3 and 4 are only 12 x 15 instead of 13 x 15 from the Flash version, so there may be some other bug going on there.

Still, this is a good sign! We only need to crank out 70 more points. If we can get this close only looking 1 move ahead, let’s plan further out.

Step 5: Just Go Harder

Early, we defined the Q-value as

\[Q(s,a) = reward(a) + Value(\text{next state})\]This is sometimes called the 1-step Q-value, because we check the value after doing 1 timestep. We can generalize this to the n-step Q-value by defining it as

\[Q(s,a_1,a_2,\cdots,a_n) = r_1 + r_2 + \cdots + r_n + Value(\text{state after n moves})\]Here each reward \(r_i\) is the points we get from doing action \(a_i\). We take the max over all sequences of \(n\) actions, run the 1st action in the best sequence, then repeat.

One natural question to ask here is, if we’ve found the best sequence of \(n\) moves, why are we only acting according to the 1st move in that sequence? Why not run all \(n\) actions from that sequence? The reason is because our value estimate is only an approximation of the true value. The sequence we found may be the best one according to that approximation, but that doesn’t make it the actual best sequence. By replanning every action, the AI can be more reactive to the true rewards it gets from the game.

This is all fine theoretically, but unfortunately an exhaustive search of 2 moves ahead is already a bit slow in my engine. This is what I get for prioritizing ease of implementation over speed, and doing everything in single-threaded Python. It is not entirely my fault though. Destruct-o-Match is genuinely a rough game for exhaustive search. The branching factor \(b\) of a game is the number of valid moves available per state. A depth \(d\) search will require considering \(b^d\) sequences of actions, exponential in the branching factor, so \(b\) is often considered a proxy for search difficulty.

To set a baseline, the branching factor of Chess averages 31 to 35 legal moves. In my analysis, the start board in Destruct-o-Match has an average of 34 legal moves. Destruct-o-Match is as expensive to search as Chess. This is actually so crazy to me, and makes me feel less bad about working on this. If people can dedicate their life to Chess, I can dedicate two weeks to a Destruct-o-Match side project.

To handle this branching factor, we can use search tree pruning. Instead of considering every possible action, at each timestep, we should consider only the \(k\) most promising actions. This could miss some potentially high reward sequences if they start with low scoring moves, but it makes it more practical to search deeper over longer sequences. This is often a worthwhile trade-off.

Quick aside: in college, I once went to a coding competition where we split into groups, and had to code the best Ntris bot in 4 hours. I handled game logic, while a teammate handled the search. Their pruned search tree algorithm destroyed everyone, winning us $500 in gift cards. It worked well then, so I was pretty confident it would work here too.

Here’s the new algorithm, assuming we prune all but the top \(k\) actions.

- From the current state, compute every possible action.

- For each action, find the next state \(s'\) and the 1-step Q-value \(Q(s,a)\).

- Sort the Q-values and discard all but the top \(k\) actions \(a_1, a_2, \cdots, a_k\).

- For each next state \(s'\), repeat steps 1-3, again only considering the best \(k\) actions from that \(s'\). When estimating Q-value, use the n-step Q-value, for the sequence of actions needed to reach the state we’re currently considering.

- By the end, we’ll have computed a ton of n-step Q-values. After hitting the max depth \(d\), stop and return the first action of the sequence with best Q-value.

If we prune to \(k\) actions in every step, this ends up costing \(b\cdot k^d\) time. There are \(k^d\) different nodes in the search tree and we need to consider the Q-values of all \(b\) actions from each node in that tree to find the best \(k\) actions for the next iteration. The main choices now are how to set \(k\) and max depth \(d\).

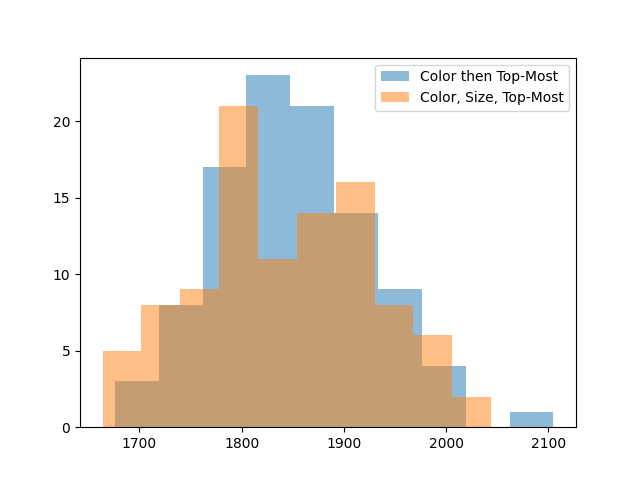

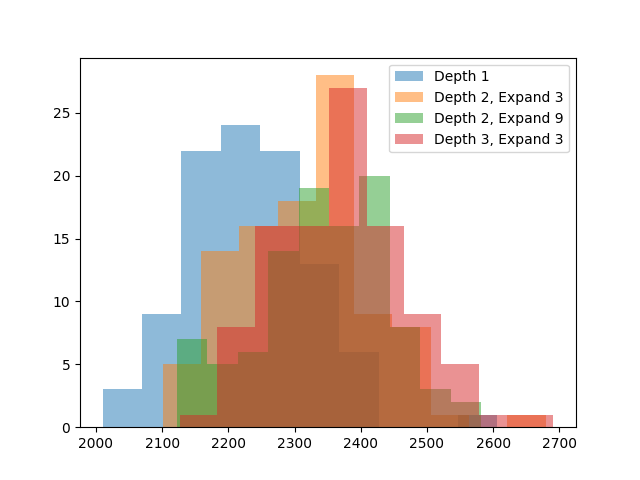

To understand the trade-off better, I did 3 runs. One with Depth=2, Expand=3, one with

Depth=2, Expand=9, and one with Depth=3, Expand=3. The first is to verify there are gains from

increasing search depth at all. The second two are 2 compute-equivalent configurations,

one searching wider and the other searching deeper.

The gains are getting harder to spot, so here are more exact averages.

Depth 1: 2233.38

Depth 2, Expand 3: 2318.32

Depth 2, Expand 9: 2343.34

Depth 3, Expand 3: 2373.37

Searching deeper does help, it is better than searching wider, and the Depth 3, Expand 3 configuration is 140 points better than the original depth 1 search.

This should be enough for an avatar score. This search is also near the limit of what I can reasonably evaluate. Due to its exponential nature, it’s very easy for search to become expensive to run. The plot above took 7 hours to simulate.

For the final real game, I decided to use Depth 3, Expand 6. There’s no eval numbers for this, but increasing the number of considered moves can only help. In local testing, Depth 3 Expand 6 took 1.5 seconds on average to pick an action on my laptop, which was just long enough to feel annoying, but short enough to not be that annoying.

After starting up the AI, I played a Destruct-o-Match game over the course of 3 hours. By my estimate, the AI was only processing for 15 minutes, and the remaining 2 hr 45 min was me manually transcribing boards into the AI and executing the moves it recommended. The final result?

An avatar score! Hooray! If I had planned ahead more, I would have saved the game state sequence to show a replay of the winning game, but I didn’t realize this until later, and I have no interest in playing another 3 hour Destruct-o-Match game.

Outtakes and Final Thoughts

You may have noticed I spent almost all my time transcribing the board for the AI. My original plan was to use computer vision to auto-convert a screenshot of the webpage into the game state. I know this is possible, but unfortunately I messed something up in my pattern-matching logic and failed to debug it. I eventually decided that fixing it would take more time than entering boards by hand, given that I was only planning to play the game 1-2 times.

After I got the avatar, I ran a full evaluation of the Depth 3, Expand 6 configuration overnight.

It averages 2426.84 points, another 53 points over the Depth 3, Expand 3 setting evaluated earlier.

Based on this, you could definitely squeeze more juice out of search if you were willing to wait longer.

Some final commentary, based on studying games played by the AI:

- Search gains many points via near-perfect clears on early levels. The AI frequently clears the first few levels with 0-3 blocks left, which adds up to a 200-300 point bonus relative to baselines that fail to perfect clear. However, it starts failing to get clear bonuses by around level 6. Based on this, I suspect Fill powerups are mostly bad until late game. Although Fills give you more material to score points with, it’s not worth it if you end with even a single extra leftover boulder that costs you 10 points later. It is only worth it once you expect to end levels with > 10 blocks left.

- The AI jumps all over the board, constantly switching between colors and groups near the top or bottom. This suggests there are a lot of intentional moves you can make to get boulders of the same color grouped together, if you’re willing to calculate it.

- The AI consistently assembles groups of 16+ boulders in the early levels. This makes early undos very strong, since they are easily worth 32-40 points each. My winning run was partly from a Multiplier in level 1, but was really carried by getting two Undos in level 2.

- Whoever designed the Flash game was a monster. In the original Flash game, you only get to proceed to the next level if you earn enough points within the current level, with the point thresholds increasing the further you get. But the AI actually earns fewer points per level as the game progresses. My AI averages 203 points in level 7 and 185 points in level 9. If the point thresholds were enforced in the HTML5 version, the AI would regularly fail by level 7 or 8.

I do wonder if I could have gotten the avatar faster by practicing Destruct-o-Match myself, instead of doing all this work. The answer is probably yes, but getting the avatar this way was definitely more fun.