Posts

-

Who is AI For?

CommentsWho is AI for right now? There are obvious use cases. Image generation for people who want filler art for work presentations, or just to mess around. Coding assistance for people who code, vibe coding for people who don’t. Speech-to-text for automatic captioning, and text-to-speech for grinding out TikTok videos that read Reddit comments to farm engagement. But also…math contest solving? Science Olympiad questions? Who is that for?

I think the easy answer to this question is that right now, AI is for the AI developers. People working in AI respect math and science contests, doing well on them is high status, so they test LLMs on those contests, even if most people do not care. It’s why so many LLM developers are focusing on code. It’s why we get announcement posts advertising that a new model is good at answering Typescript questions. Code is useful, it makes money, it is a testbed for AI speeding up the development of AI, and it is easy. Not in it being easy to improve coding, but in it being easy to evaluate. In this era, if it isn’t easy to evaluate, you have no hope. Should we be surprised that people who write code can tell what models are good at coding? Did we focus on code because it was the best thing to do, or because it was the closest thing that seemed approachable?

People have argued that teaching models to reason in math, code, and science domains generalizes to reasoning elsewhere. To be clear, those arguments are bearing fruit. Yet it doesn’t feel like the only path we could have taken. We say we want our AI to be truth-seeking, and then define truth-seeking as passing unit tests.

Recently, I sharpened a #2 pencil and took the history section of “Humanity’s Last Exam.” Consisting of 3,000 extremely difficult questions, the test is intended for AI, not me. According to its creators and contributors, Humanity’s Last Exam will tell us when artificial general intelligence has arrived to supersede human beings, once a brilliant bot scores an A. […] Of the thousands of questions on the test, a mere 16 are on history. By comparison, over 1,200 are on mathematics. This is a rather rude ratio for a purported Test of All Human Knowledge.

Asking Good Questions is Harder Than Giving Great Answers, by Dan Cohen

If CGP Grey videos have taught me anything, we should have been asking the historians what it means for something to be true. Or philosophers, if the point was to build rigorous arguments in natural language. The story of philosophy is people writing increasingly nitpicky arguments attacking imperfect, imprecise definitions of how to view the world. Not that that’s my cup of tea, but if people in another universe got reasoning to work with a DeepConfucius or OpenAristotle model instead, I wouldn’t have been surprised.

People talk about \(p(doom)\), but not \(p(good)\) or \(p(thrive)\). It’s as if people assume \(p(good)\) is exactly \({1 - p(doom)}\), that any case outside the worst case will be amazing for the world. I don’t think people make this assumption explicitly, it’s just in the way people talk. No one would seriously think this on reflection, right?

I’m working in AI because it pays well and is potentially really good for the world. The x-risk questions are worth consideration. But I would claim that even assuming the existential risk questions are overblown, AI’s not going to be good for the world unless we (the field) proactively work for it. I think that requires more engagement with outsiders and more intentional choices of domains to focus on than we’ve done so far.

When OpenAI first announced their video generation model, Sora, they gave closed beta access to a few filmmakers to see what they made of it. The result was that it didn’t help much, because the model didn’t understand the filmmakers, because it wasn’t in the data and OpenAI devs never spotted it as an issue.

With cinematic shots, the ideas of ‘tracking’, ‘panning’, ’tilting’ or ‘pushing in’ are all not terms or concepts captured by metadata. As much as object permanency is critical for shot production, so is being able to describe a shot, which Patrick noted was not initially in SORA. “Nine different people will have nine different ideas of how to describe a shot on a film set. And the (OpenAI) researchers, before they approached artists to play with the tool, hadn’t really been thinking like filmmakers.” Shy Kids knew that their access was very early, but “the initial version about camera angles was kind of random.” Whether or not SORA was actually going to register the prompt request or understand it was unknown as the researchers had just been focused on image generation. Shy Kids were almost shocked by how much the OpenAI was surprised by this request. “But I guess when you’re in the silo of just being researchers, and not thinking about how storytellers are going to use it… SORA is improving, but I would still say the control is not quite there. You can put in a ‘Camera Pan’ and I think you’d get it six out of 10 times.”

Actually Using Sora, by Mike Seymour

To be fair, I assume Sora is better at this now, given that this article was from last year. OpenAI deserves props for asking for feedback in the first place, because many do not.

I’ve lurked in a few fan art communities in my time. The artists did not know what AI was, but when they learned, they quickly decided they did not want it. But we automate art because we can, and it’s easier than learning to do the plumbing. Do the plumbers want AI? Genuinely, I don’t know. Maybe someone should ask them.

Things move fast in AI, and we’ve speedrun the journey from cute toy to symbol of capitalism and big tech in record time. If people expect their benevolent AGI to cure cancer, stop aging, and open up new vistas of knowledge, it’d be real cool if we make sure that’s actually something we focus on. Since right now, I’m not convinced we are. It feels like the most likely outcome is that people go all-in on pushing raw intelligence, in the way that AI developers can measure it, leaving behind those that are not like AI developers. We’ll follow the path of easy-to-generate text rather than text that encourages a better life, take the road of whatever gives the best PR, and eventually marvel when we create the final victory of capital over labor. It doesn’t feel like a great path to me. I don’t know how much power I have to change that path. I just feel some notion to make it a little better.

-

MIT Mystery Hunt 2025

CommentsThis has spoilers for MIT Mystery Hunt 2025. Spoilers are not labeled or hidden.

I feel I have been slower about this year’s post than last year’s. There are no deadlines here, but last year I got my post done before TTBNL’s AMA, and I only started on this post by the time Death & Mayhem did theirs.

To spoil the answer to this puzzle, Death & Mayhem have been impressively on top of things, hosting their AMA the Wednesday after Hunt, and being on top of things was just a running theme. This year’s Hunt was really solid. I enjoyed it more than their 2018 Hunt, which is commonly cited as an all-time good Mystery Hunt. In part that’s because I was remote in 2018, so I missed all the in-person energy from that year, but I do think the rounds from 2025 rivaled some of the concepts from 2018. One of the hypest things you can do in a puzzlehunt is backsolve a meta, so of course I would like the hunt where we backsolved five of them. (And they weren’t even all Shell metas!)

It did make me a little wistful about writing 2023’s Mystery Hunt. A lot of 2023’s writing goals were to write something analogous to 2018 (fewer puzzles, weird and difficult metas, go all-in on what teammate values, scale down Hunt). I know it’s stupid and doesn’t make sense, but throughout the weekend I was thinking “dang, this is what could have been if we’d executed better”.

During wrap-up, Death & Mayhem said they were “a little bit capital E Extra in everything we do”, and, yes, that came through. It was great, 10/10, very strong theater kid energy, like Death & Mayhem had charged up 7 years of power level and went nuts once they got to write Hunt again.

From Paranatural

High-Level Thoughts

Hunt was won at a reasonable time. Sunday 11:47 AM, hooray! That being said, it still felt long because Cardinality won so far ahead of everyone else. Would definitely have preferred Hunt go shorter by another few hours, but can’t complain too much.

The decision to give every team a radio was insane, very cool, and probably should not be repeated. I did not do any radio puzzles besides listening to the weather (more on that later), but we did break our radio when we plugged it into charging while the radio was still on. We got it fixed, but it was indicative of how much of a headache it looked like to support.

The Gala made a lot of sense in-story, and I would echo that it was great to run into hunters from other teams during the few times I visited. I’m not sure how many people it took to staff, but I would like something similar to come back.

Story-wise, I think it’s just hard to tell a story within a puzzlehunt. You have much more success if you instead focus on conveying a certain vibe or aesthetic, and then let that aesthetic carry the plot for people interested in the story. In that respect, I feel this hunt delivered the crime noir aesthetic really well, even if I didn’t fully remember everyone’s name or secret.

As for the unlocks…

Choose-Your-Own-Adventure

I think if you want to do a choose-your-own adventure unlock system, this Hunt was a good implementation of it, and showcased its strengths. The choices were informed, so teams could solve the puzzles that sounded exciting to them. It enabled a lot of strategizing on whether to go all-in on one round or spread out. It is much more likely that every puzzle is worked on by many teams, rather than the final feeders in unlock order getting shafted.

The open-world nature of Breath of the Wild was brought up as inspiration, but that invites the main criticism of Breath of the Wild. Since there is little guarantee on shrine order, most shrines in Breath of the Wild are flat in difficulty, complexity, and reward. It is much more interesting to find a shrine than to complete it. In this Mystery Hunt it was reversed, where the act of unlocking is easy but the value and difficulty of a feeder varied. Sometimes you open a puzzle that’s harder than expected and just go down 1 width. (Looking at you, Do the Manual Calculations.)

I had a lot of fun with the choose-your-own-unlocks. I am not sure if our hunt ops team felt the same way? To borrow a metaphor from Defunctland’s FastPass video, some people enjoy planning their trip to Disney World, and some people just want to go to Disney World. My experience was much closer to the “go to Disney World” side. I saw puzzles get unlocked, with no idea what round they were in, and I worked on them because I assumed hunt ops was only unlocking puzzles that helped Hunt progression. Meanwhile, the first reaction of our hunt ops to the key system was “this is going to be a disaster”, since it added lots of tiny decisions on top of their existing large scale decisions. I do hope it was a fun disaster, rather than a real disaster.

The eventual teammate key system was this:

- Hunt ops owns all the keys and clues. No one else gets to use them unless hunt ops says it’s okay.

- The owner of our Hunt management system modified their bot to send a Discord alert whenever we revealed a new puzzle.

- Team members asynchronously vote on puzzles they want to work on, where a vote means you will actually work on it, rather than watch other people work on it.

- Keys will be spent based on votes made, taking round prioritization into account. Ping hunt ops if keys haven’t been used in a while.

- Hunt ops planned to convert the 1st clue to keys, then reassess.

This was all pretty uncontroversial. Where it got controversial was when we got our 2nd clue, hunt ops did a discussion, and declared that we would be saving all future clues to push feeders in endgame metas. After failing to finish last year, we were pretty determined to finish this year, and optimized for that outcome. As we progressed through the Hunt, exciting sounding puzzles would sit there, being unlockable if we cashed in clues. This was exacerbated when hunt ops decided to stockpile 3 keys after we’d made some progress on the Illegal Search meta. The reason they did so was because they strongly suspected more puzzles were gated behind Papa’s Bookcase (“clearly the bookcase of an escape room will hide another room”), and stockpiling would let us immediately push further progression in the round and avoid stalling out. This was a correct prediction, and getting an instant 3 unlocks post-Bookcase definitely contributed to us finishing that round early. The problem was that they didn’t tell everybody this was the plan. So multiple people saw that we had keys, and weren’t using them even on reminder ping, when hype puzzles like The 10000-Sheet Excel File weren’t getting unlocked…

Personally, I never felt like I ran out of puzzles to work on. There was always something in motion that I could contribute to, and puzzles were big enough that 4+ people could work on them productively. However, I did notice that we never really had a puzzle that sat untouched for a long time, like I’d seen in past Mystery Hunts. Based on asking other teams, teammate was on the low end for clue to key conversion. We converted 1, Cardinality converted 2, Galactic converted 3 and regretted converting the 3rd, Unicode Equivalence converted 3 and also regretted it, Providence converted 3 and didn’t regret it, TSBI converted 3, Setec converted 4. It worked out for us, but I can totally see how it would have been more fun to just unlock all the things.

Choose-your-own-unlocks have had two good showings this year and in 2018, but I’d be hesitant to say that’s evidence for it as the default. The data is not that it works, it’s that it works if you’re Death & Mayhem and have 100+ people helping out on the week of Hunt. I have enjoyed all the Huntinalities, so I trust Cardinality whatever they choose.

Pre-Hunt

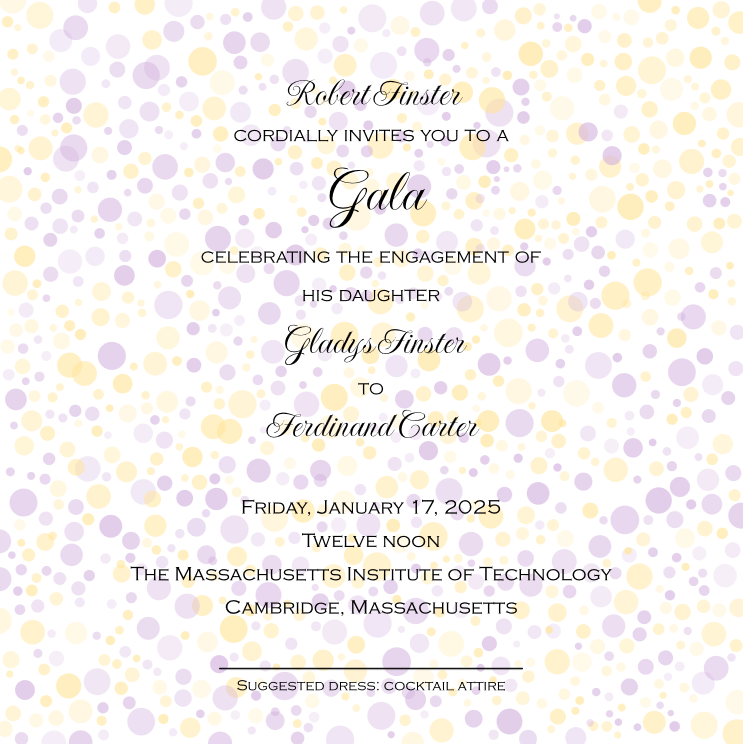

Our story begins with the Gala invitation.

In previous years, teammate has tried to solve puzzles from pre-Hunt material. Every time, they were not a puzzle. After doing this for 5 years, we’ve stopped trying. The general thinking was that the Gala invitation was a puzzle, but it wouldn’t be solvable without shell from the main Hunt.

When we eventually did unlock the invitation puzzle, and found it had no shell, we were surprised. Supposedly Cardinality pre-solved the puzzle because “teammate is definitely going to pre-solve it and if we don’t we’ll be behind”. Sorry to let you down? We also failed to pre-solve the Dan Katz Puzzle Corner.

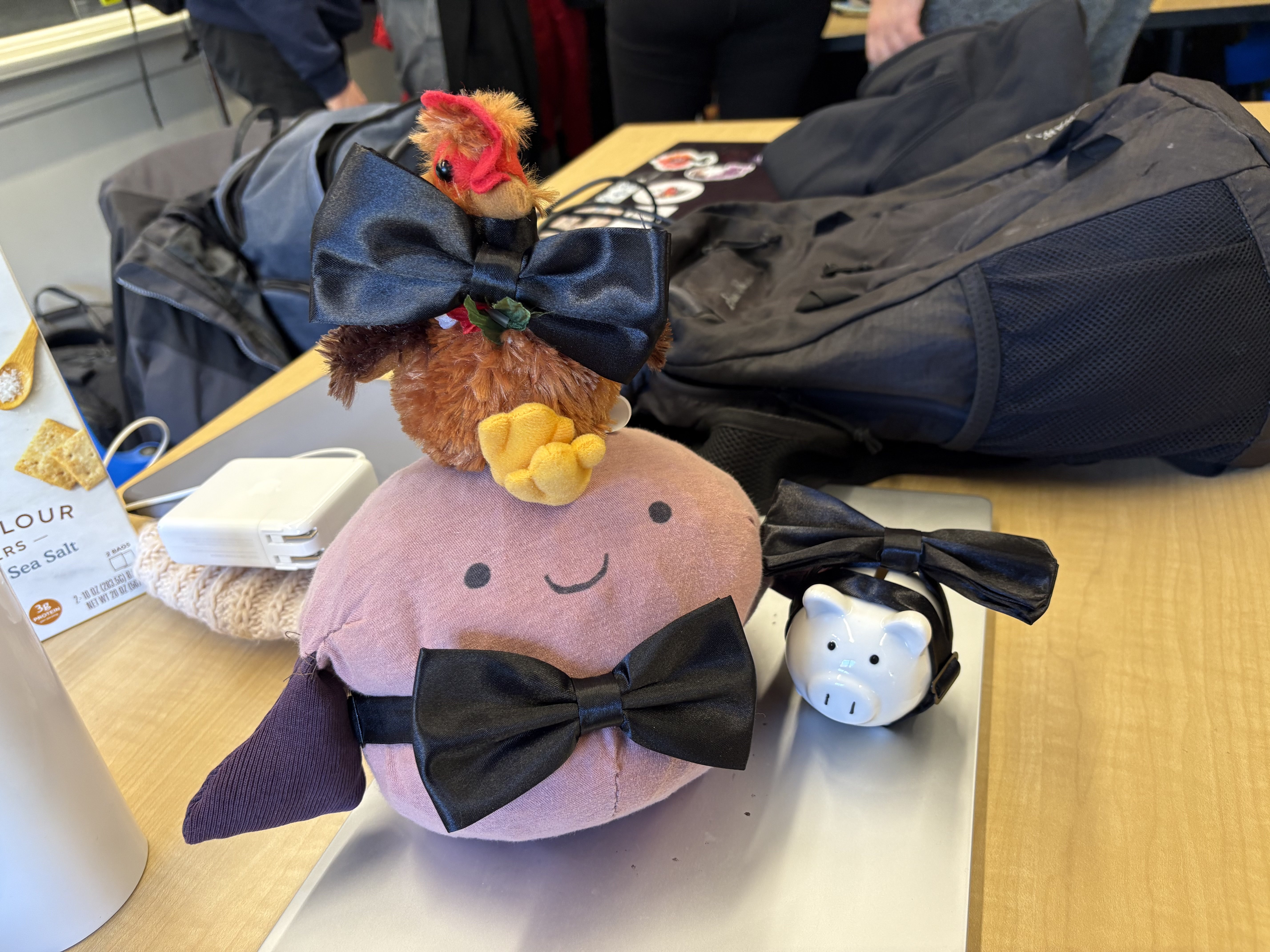

Ignoring the puzzles for a bit, the invite suggested cocktail attire. This was very convenient for me, since I was attending a wedding before Hunt. (The couple specifically picked the week before Hunt because many of their friends are puzzle people.) That made it incredibly low effort to show up to kick-off dressed up. teammate did a group order of bowties as well. Did you know you can buy boxes of 40 bowties for $25 on Amazon? It was surprisingly cheap to play along.

I did have to figure out how to get my blazer to Boston without wrinkling it in my carry-on. The solution was to be stylish and wear it on my person, which meant I also dressed up at wrap-up and in the airport.

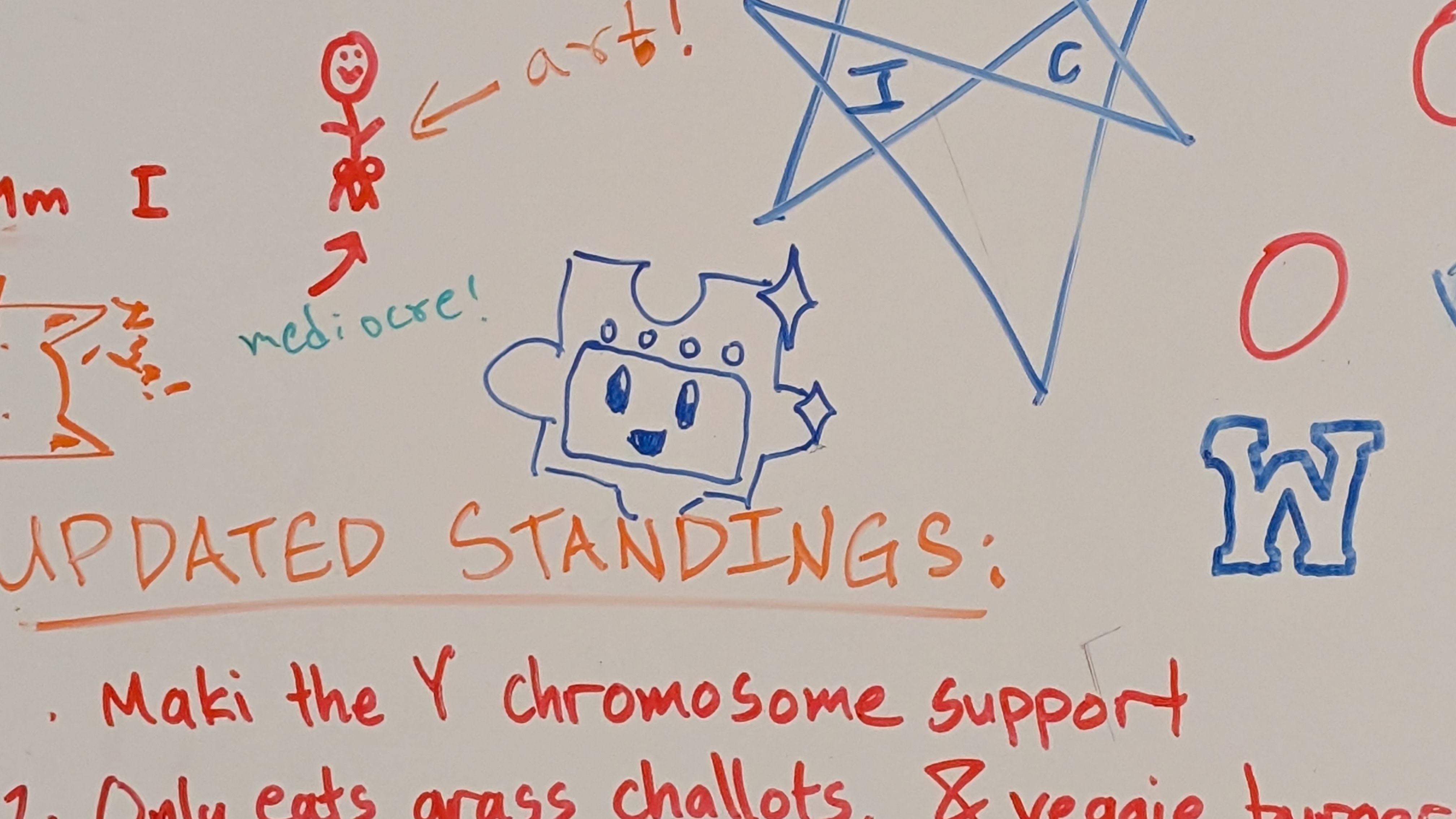

In my free time pre-Hunt, I went to Puzzled Pint, where I tried to all-brain a logic puzzle (solve it without writing anything). This was a terrible idea. I also went to some museums in the area, and got involved in a heated argument about vegetables in the teammate Discord. It is not worth re-litigating, but my takeaways are that some vegetarians dislike salads, people like vegetables more if they’re cooked (shocker), and “screw zodiac signs, what vegetable are you?”

Friday

After kickoff finished, we went to our on-campus classrooms, and puzzle release went off without a hitch. Honestly, I’m not sure why no team has thought of “don’t refresh the page, let it live update” before. It’s such a good idea.

Missing Diamond

XOXO - This was our first solve of the Hunt (hooray for the Activity Log to make checking this easy). I will always be proud that we outraced the logic puzzlers working on Unreal Islands. Identified two pairs then focused on transcribing pairs into the grid for extraction.

Downright Backwards - By the time I got to this puzzle, the entire grid had been filled out, and my one contribution was asking if we should try the opposite interpretation of the z-direction (which was correct).

Battle Factory - I have been watching some Gen III Battle Factory speedruns recently. Luckily this puzzle got solved faster than those speedruns, with much less RNG. This is a cute idea, I’m surprised I haven’t seen it before.

📑🍝 - I did not work on this puzzle, but got many confusing DMs until I understood what was going on. This turned into an interesting litmus test for how other teams were doing, based on when they asked for 🍝.

🔎🧊 - A little annoyed with the final extraction step of this puzzle (really wanted it to be only adjacent letters, rather than any pair), but I liked everything before it. This was the first puzzle I did coding for this Hunt, to brute force finding the words. There was a clean way to implement it, and the way I did it (8 nested for loops).

Zing it Again - The first set we found was Weird Al (as expected). We found the Bob’s Burgers set pretty soon afterwards, but could not find the HM set for a long time. I was pretty happy about breaking into that one, definitely enjoyed the B-B-B-BAD TO THE CHROME rebus.

The Boardwalk - I worked on all the metas in Missing Diamond, because, well, I like working on metas. I didn’t come up with any of the extraction ideas for this meta, instead I did advocating for the ideas I did like. Took us longer than it should have to find THE BEATLES, because we didn’t realize The Beatles Collectors Edition could have a space for THE BEATLES. We also expected letters to get extracted from the entire board, and assumed we were missing feeders since all our letters were only in one half. Luckily, one person decided to submit exactly what was in the sheet from the 5/5 feeders we had.

Also, I don’t think anyone else has mentioned this: it’s kinda insane Death & Mayhem implemented 3 minigames just for the Boardwalk story interaction? Like, what? I tapped into my God Gamer genes and won all of them. They don’t seem to be replayable, hope they make it to the archive!

The Jewelry Store - The meta crew next looked at The Jewelry Store, breaking in pretty quickly. Interestingly, when we broke in, all of our 5/7 feeders were adjacent in the chain. That hurt the wheel of fortune attempts, and we needed a 6th feeder to solve it. I thought the backsolve would be easy, but there was a surprisingly large set of valid answers and we ended up forward solving the last feeder.

The Art Gallery - When I started looking at this meta, we’d already IDed the Crayola and RGB steps. Another teammate did a sort by length, and I noticed the UNICODES partial. From there it still took us a while. I refuse to believe there’s a good canonical source for this, we tried both Wikipedia and the Crayola fandom page and they gave conflicting data. At one point, I decided the most canonical source would be to use an eyedropper tool on colors from the crayola.com website, but then that was inconsistent too and not the one used for the puzzle! (At least for Flamingo Pink.) Our solve relied on putting all the options into different spreadsheet tabs and squinting until an answer came out.

(Aside: for the Art Gallery interaction, we were asked to investigate Papa’s secret, which was in either his wallet, his office, his car, or his study. It was set up as a forced choice, where only one option would progress the story. I know this because we voted for every other option first. I want it on the record that I voted for the correct option every time, who keeps their deepest secrets in their car, why did so many people vote for that.)

On the Corner - We knew this puzzle went to Art Gallery, which we’d solved. The backsolve had failed, and eventually we said “how hard can it be to forward solve a puzzle?” My contribution was 1) working on the Tech Corner puzzles while 2) not noticing that all 4 Tech Corner puzzles had already been solved in another tab. I assumed Dan Katz was in on it and it’s so funny he wasn’t.

The Casino - We were down to our final Missing Diamond meta. I noticed all our feeders contained a card value, started with a suit letter (C/D/H/S), and ended with a suit letter (C/D/H/S). From this, we concluded that each answer defined two hole cards. One was the number + suit from the last letter. The second was an undetermined number + suit of first letter, and we would find that number based on what worked for the given hands.

Now, that’s not exactly how the meta works…we had 5/7 feeders and it just so happened that we were missing the two feeders that would have broken the pattern. After failing to solve, we decided to go get another feeder.

Be Kind, Rewind - This puzzle definitely reminded me of the similar one from Puzzle University, but that puzzle was fun and so was this one. I was drawn to this puzzle for the movie ID, but then it turned into more than that. I am very thankful that although teammate is young, they are still old enough to know what Blockbuster was. I don’t need to feel any older from Mystery Hunt.

The Casino, Revisited - Now that we had an answer breaking the pattern, we thought more about how to use the cards. Looking at the most constrained hand (10♠/A♠ or 9♠/10♠), I noticed we had both of 10♠ and A♠ in our answers, and had no diamonds (which was good for uniqueness of the first hand). I proposed the correct idea and we solved pretty quickly, backsolving No Notes to clean up the round. At wrap-up, we wondered why our team wasn’t in the team photo montage, and that would be because we backsolved the submission puzzle for it. Oops.

The Thief - Paraphrased version of our solve: two people go out with the radio, returning an hour later.

“Yeah, we’ve followed the entire path but don’t really know what to do with it.”

“You know about the grid on the round page and all the witness statements we’ve been collecting in the spreadsheet, right?”

“…What?”

Stakeout

I spent most of my Hunt working on the tougher, meatier puzzles, so I did not spend much time in the Stakeout round. Stakeout width was deliberately kept low (around 1-2 until meta unlock, then 0 after Chinatown unlocked). I joked that we were practicing sustainable fishing.

The Ultimate Insult - Man, I opened this puzzle a few minutes after it had unlocked and it was already done. I’d like to think our 6 minute solve was the fastest, but I bet some other video gaming team did it in 5.

Fight Night at Mo’s - This puzzle felt a little weird. Once we broke in, we started unrolling the bracket, but then realized all the extraction notes were either in round 1 or the finals, meaning you could ignore almost all the matches. I initially thought this would be about Moe’s Tavern, but nope, that was a different puzzle.

Control Room - I stopped by this puzzle to spectate the madness. We assumed “rotate the camera” was going to be meaner than it was. Our expectation was that our remote camera view would rotate by 180 degrees, and we’d have to do all future directions from an upside-down camera feed.

Some Assembly Required - I see we’ve continued the meme of having a puzzle named “Some Assembly Required”, from 2023 to 2024 and now 2025. I’m looking forward to solving “No Assembly Required” in Mystery Hunt 2026, a puzzle that gives you the answer for no work.

Background Check (Friday)

He Shouldn’t Have Eaten The Apple - When solving this puzzle, the first location we IDed was Adam’s Peak, which inspired many Adam conspiracies, like trying to make Tomb of Adham Khan work. We eventually got out of this rabbit hole by finding the UNESCO connection. We skipped the step of putting the locations on the map, by guessing the correct sort order. I will say, it took us a long time to get the joke of “they are all ruins”, it felt pretty unmotivated before that and only tenuously motivated after that. Still, if you have an in with Adam Conover, you gotta use it.

Paper Trail (Friday)

World’s Largest Crossword Puzzle - Author of World’s Largest Logic Puzzle: “I feel like if I don’t work on this puzzle, I will have committed a crime.”

My contributions were 1) pointing out the clues for “Zero” and “One” were bolded, clearly indicating how input worked, 2) solving both clues incorrectly with NULLED and UNIQUE, and 3) leaving for another puzzle, making my contribution worse than useless.

At some point during the solve, the author of WLLP shot down an idea saying “It can’t be that, because when I tried constructing that idea, it was impossible.” Just a truly deranged solve. teammate solved this in 2 hours, and I am pretty confident that will be fastest solve once more detailed stats are out.

Illegal Escape (Friday)

By the time I understood the round gimmick, we’d already applied all the operations. It’s a cool concept for a round, that I mostly missed, but you can’t see every cool thing during Mystery Hunt weekend.

(A Puzzle of the Dead) - This puzzle was annoying to transcribe data for, but quite solid all the way through. Each section takes 40 seconds to display, and there are 8 sections to see, which added up. Once we got the message for the first destruction’s encoding, I failed to find the online decoder for it, using a jank Python script I found instead. “What could go wrong with executing arbitrary code from the Internet?”

Once we got to the rhyme scheme step, I suggested that it could work like Reflections on a Milky Steed Who’s Quite Amphibious, Indeed. With the comment that “15 years is long enough to reuse an idea”, two of us put in the letters, getting excited that we’d hit exactly 26 rhymes. Unfortunately, we had some data errors. We flailed until the Saturday 1 AM cutoff, and I took a look in my hotel room for a bit before going to bed. It got solved the next morning when someone checked our work. It’s not until I read the author’s notes that I realized the poems were constrained to not use the letters U or O. Props on the construction, that sounds so painful.

Murder in MITropolis (Friday)

esTIMation dot jpg - It was interesting to break into this overnight. But first, let me backup a bit.

At time of unlock, we had time to send 2 groups, one at 11 PM and one at midnight. Our first group got wrecked due to lack of MIT knowledge, so we remade our second group to have more former MIT students and they did better. They also said the Friday midnight esTIMation was incredibly lit - I heard someone got engaged 15 minutes before the interaction? Wild.

Overnight, some images from esTIMation were posted to our #crowdsource channel. I was working on (A Puzzle of the Dead) at the time, but took a look and successfully IDed two of them. This baited me into doing another hour of image searches, but I didn’t find any more matches.

Saturday

Murder in MITropolis (Saturday)

esTIMation dot jpg - We sent two more groups of people, at 8 AM and 9 AM. These were considerably less lit than the midnight run. With 2 more visits of data, and more fresh eyes, we successfully nutrimaticed the answer from 6/17 letters, right before our 10 AM group went for round 5.

Give This Grid a Shake - As we solved the crossword clues, I looked in my folder of past puzzlehunting scripts, and found a file called

boggle_bash.py. While other teammates worked on building the Boggle board by hand, I did code archaeology to investigate what this script did. After reading, I determined my script constructed 4x4 Boggle grids from a list of contained words, which was exactly what we needed. I put in the constraints, it output the correct 4x4 grid in 25 seconds, and I put it in the sheet. I was told I absolutely had to tell this story in my blog post, so there you go. (The epilogue no one else knows is that I then tried to modify it to solve the full 6x6 board, but it got handsolved before I could make all the required changes.)At the time, I didn’t know why I had this script, but now I do. Four years ago, we suspected a metapuzzle worked via Boggle, so I wrote this script to try to generate all possible boards given some missing feeders. The script didn’t work, because the meta wasn’t Boggle based. I’m glad my work was useful 4 years later!

We Can Do This All Day - It was not until wrap-up that I learned this was not intended to be the obligatory scavenger hunt. Before then, I’d discussed it with a teammate as an interesting innovation on how to make the scavenger hunt less grindy, while maintaining the seat-of-your-pants bullshitting that makes the scavenger hunt fun.

I am overall ambivalent on the scavenger hunt, I think it’s fun but it’s always fighting the tightrope of taking too much time to prepare entries for. We solved this by prerecording each task at multiple locations before calling Death & Mayhem for our 2nd attempt.

Engagements and Other Crimes - As mentioned earlier, we did not presolve this puzzle, but we did bring the original invitation keepsake, so we didn’t have to print it. Which was good, because our access to printing was pretty low this year, given many MIT students had aged out and were now just alumni. We did end up printing another copy anyways.

A Map and a Shade (or Four) - On initial unlock, the person who spent the key said “oh no, this was a scam”. I took a look and said it wasn’t obviously a scam, since it was definitely something with US states and four coloring. We sat down and started making some derivations. Then, Jargon got unlocked.

Illegal Escape (Saturday)

Jargon - Literally everyone at my table said “LINGO PUZZLE” and left me to the geography wolves. I decided I could not defeat the geography wolves on my own, and bravely retreated to Jargon as well. This got started by like 10 people simultaneously - most of my contribution was repeatedly pinging people to come to our table instead, since we’d had the most progress and relaying info in the sheet was way less efficient than crowding around 1 computer.

During this, A Map and a Shade (or Four) had gotten picked up by another group. Once we’d finished Jargon, I decided that actually I didn’t need to work on a US geography logic puzzle, and moved to something else.

Murder in MITropolis (Saturday, Part 2)

Beyond a Shadow of a Doubt - This one was nice. The main idea comes together pretty elegantly, but the actual grinding is really non-trivial even if you know what you’re doing. Potentially we could have jumped to the final dropquote and solved around the missing info, but we ended up solving it sequentially and I proposed the final correct idea for how to use the colors.

The Killer - I helped on IDing a few pages (the ones for Wonderland and Berkeley), but then moved to other puzzles. Only now do I understand the calls for a Morse code nutrimatic. I’m guessing someone did implement one by Hunt end.

Background Check (Saturday)

The Tunnels Beneath the Institute - This was, just, like, the weirdest dataset. Finding the AC Installation Tutorial genuinely broke me. We did not go far enough to get to the central a-ha, as I was instead baiting into searching a different cursed dataset from…

Story Vision Contest - This puzzle was pretty fun, it’s surprising how much overlap there is between the two datasets. My introduction to this puzzle was “here’s a clue that talks about churning butter, which you’d think would be from a fairy tale, but is actually from Poland’s 2014 Eurovision song where a sexy model churns butter in the choreography.” We sped up a lot of the song ID by guessing the puzzle would use the most famous or popular performances from each country. The motif IDing afterward was a bit less fun, but we got through it before it got stale.

Alias - I didn’t do anything for this metameta. I just wanted to mention that teammate backsolved The Mark, then guessed the correct metameta pun from 2/3 pieces on the first try. Background Check meta team was cracked.

Paper Trail (Saturday)

Of the later rounds, I spent the most time on this one, both on feeders and the metas.

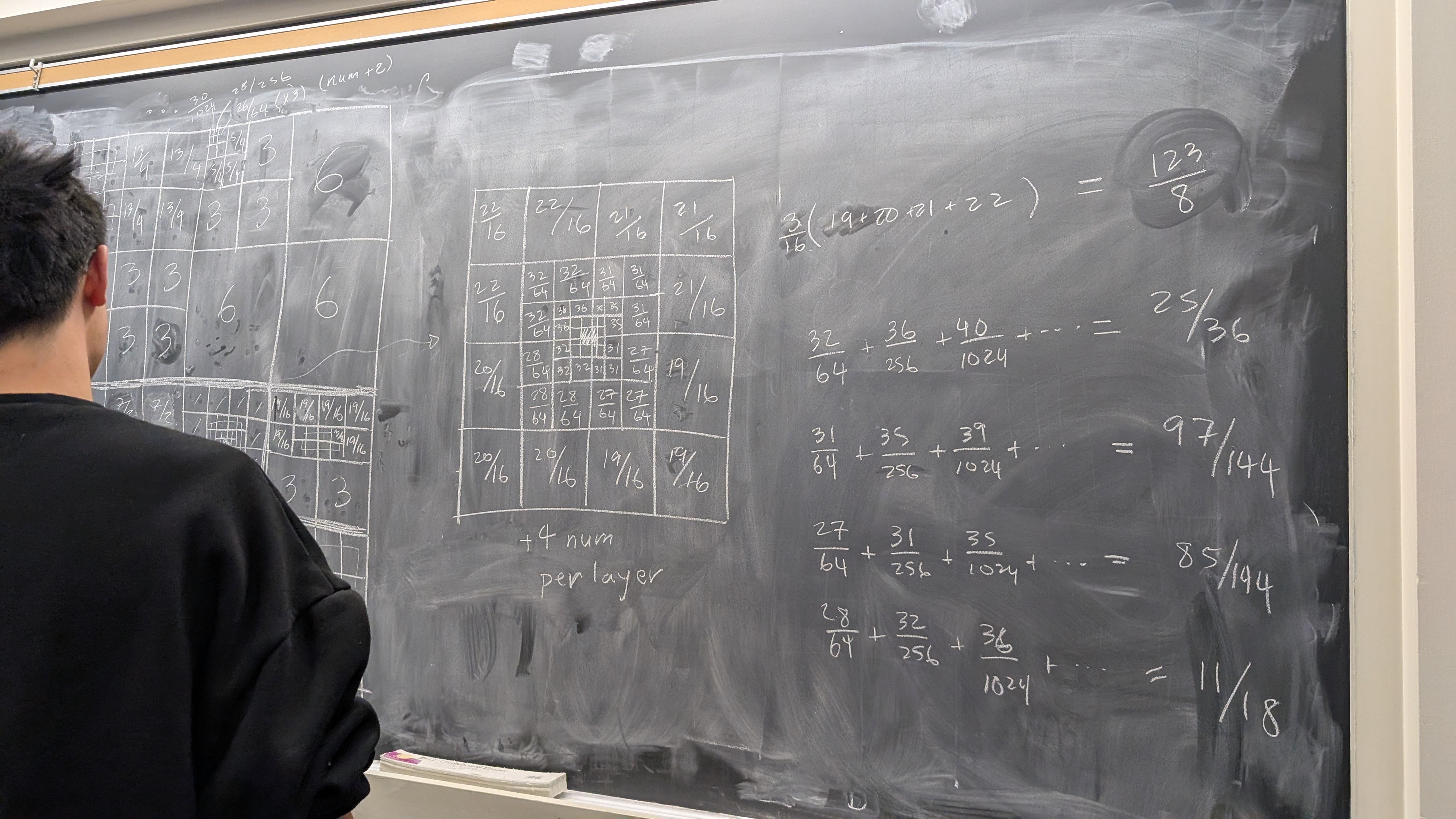

Do The Manual Calculations (Don’t Try Monte Carlo) - I ran far, far away from this puzzle. We filled up two blackboards with calculations, getting to the CORRECT partial on Friday, but did not solve until Saturday. Long story short, there was a mistake in an earlier board that still extracted the right letter for the CORRECT checksum, so much of Friday was spent with an incorrect grid that didn’t work for the puzzle. This took a long time to notice and fix.

Follow the Rules - I jumped onto this puzzle because I had just come off doing a bunch of research puzzles and wanted to poke a black box. We got 7 of the rules, but couldn’t find a consistent explanation for the last 2. To handle this, we turned to brute force with code, since \(3^9\) is plenty small enough.

Ignoring the two missing rules, there were 38 solutions. Four of us split up the work manually checking which one solved the puzzle, by which I mean, one of us said “oh, I got it” on the first solution they tried, and the rest of us checked another 15 solutions to convince ourselves the solution was unique. It was unique, that person was just insanely lucky.

We still didn’t know the last two rules, but one person pushed for generating all trigram constraints for each section, assuming it used ternary. The first section extracted CAL and they were adamant it would continue LIN for CALL IN and so forth. I thought this would be too messy to do (you’d get 40 trigrams per set for some ugly regex), but then they pointed out you could verify each section on the website even if you don’t understand all the rules, as long as you mentally apply the permutation on the website’s output. That was enough to finish the puzzle.

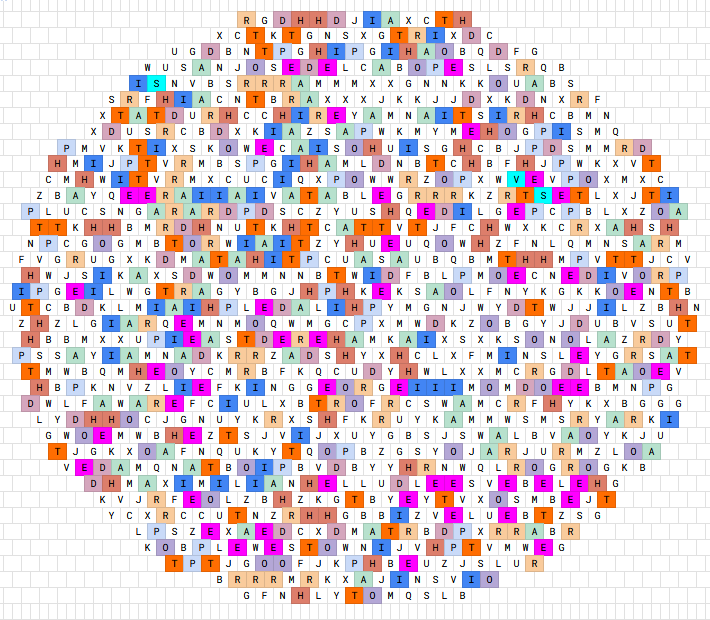

Star Crossed - We got through the first step of the puzzle without too much issue, although we were stuck on “SHTBYELEVEN” for a bit, trying to turn it into a final cluephrase (SHOT BY?). As one of us left to go talk with hunt ops, they said “this can’t just be a word search, that would be lame”. I realized it could be “SHIFT BY” instead. That was confirmed by the answer checker, so we kept going.

The policy on confirming partials has become more lenient over years of Mystery Hunt. This is partly because of the shift to automated answer checking, but it’s also likely driven by broad trends in the adjacent field of escape room design. Rooms have moved from advertising their low finish % to advertising how fun they are. People prefer confirmation on their partial progress more than the abstract idea of only submitting answers when you are confident you are done. I think this is fine? Partials getting confirmed haven’t stopped people from writing good puzzles.

We did the shift, did the next step, got the “find names of Venus” message, and then got stuck. The only names we’d be able to find were ISHTAR and VESPER. Although we suspected the puzzle would continue to use 6-long names of Venus, we just could not find more. In a bid to try to make more famous options like APHRODITE work, I created a conditional formatting version of the grid with APHRODITE letters colored, which was…not so helpful.

We abandoned the puzzle, with notes to try finding more names of Venus, and some fresh eyes did the grunt work for the solve a few hours later.

A Weathered Note - Throughout Hunt, we had written down the weather reports coming in, but we had done a really half-assed job of it since there was always something more pressing. (We includes me here, my scrawl for Stockholm was unreadable.) I was hyped to finally use the weather data, but our data was low enough quality that it was better to begin from scratch. This turned the start of the puzzle into the world’s goofiest Pomodoro - 25 minutes of research about weather telegram codes from the late 1880s, then short breaks to transcribe the weather. Every time the weather came in, we would shout “WEATHER!” to get the room to be quiet. Unfortunately, the puzzle solve jingle was louder than the weather broadcast…

Fortunately (unfortunately?), the time it took us to find and understand the 1887 War Department Weather Code was long enough that we were never bottlenecked on weather reports. Our bottleneck was what you’d call a “skill issue”. We got up to the last step, but failed to figure out the correct interpretation of “retiring after this last transmission” and got stuck. When the Shell Corporations got unlocked, I abandoned the weather in favor of those shells. We solved the puzzle on Sunday after getting a hint.

Despite getting stuck, I think the cluing was fair and this was one of my favorite puzzles from Hunt. In an absurdist way, it was so fun to tell people “SHUT UP I REALLY NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE WEATHER”, and the relevant documents were just the right level of obscure.

(I think there’s actually a small mistake in the solution too? For Los Angeles, the river is rising at -1’, 6 tenths. I translated this as JAY rather than JAMES. My interpretation of the pg 65 river report table is that for negative values, you should read each section backwards, lines after the bolded -N foot header are for -(N-1) K tenths. This is consistent with the height of the river ascending as you go down the page, and makes JAY be -1’ 6 tenths with JAMES as -0’ 6 tenths. The reason I believe this interpretation is because the alternate one makes it impossible to encode -0’ 6 tenths. This mistake didn’t really affect solvability, we solved that clue correctly with JAY.)

Shell Corporations - In conjunction with the metameta, these were definitely the highlight of my Mystery Hunt. Soon after we unlocked the shells, Death & Mayhem came by for a team check-up, asking about our meta progress in particular. We delightfully told them our progress on The Killer was “54 PDFs”. The narrator for the weather was part of the check-up team, and we jokingly asked if we could hear the weather in Los Angeles.

“Sorry, there are union rules. I can only give you the weather at very particular times.”

“We’ll pay you triple your rate!”

“I get paid $0, so that’s not a lot.”

“…Your union needs to negotiate better.”

The people working on The Killer debated what they could ask about their work, but we were quickly told that we were absolutely not getting hints on anything, which let us know we were doing well. We continued work on the shells, solving Shell 1 forward and solving Shell 3 with 0 feeders via a Vigenere brute-force, but failed to progress further. Late in the night, we broke into the mechanic for Shell 6, and I spent my hotel room evening trying to construct cryptics without much success.

Sunday

I would end up spending my entire Sunday on Paper Trail, because once we broke into the shells, it was too exciting to do anything else.

Paper Trail (Sunday)

Shell Corporations - When I arrived, we were very confident something weird was up, but weren’t sure exactly what. The metas just felt too much like spaghetti, reminiscent of Pokemon and Sci-Fi metas written around tight constraints. I even looked at AllSpark in hopes it would help us solve Shell 5.

Our leading guess was something like, “there is a backsolved feeder we can’t submit like Safari Adventure, and also feeders go to multiple shells”, based on the feeder count and us really liking PENROSE for Shell 1 but not succeeding on any backsolve. Meanwhile, all our Shell 6 work was on the wrong track thanks to an early guess on RANGE that was entirely incorrect.

At this time, HQ called us and said we could now ask for hints. We knew Cardinality was about to finish thanks to seeing literally their entire team in the Gala, so I took the opportunity to get the hint we desperately needed for A Weathered Note and came back in hopes the extra answer would let us break in on a new Shell.

By now, we had divided our HQ into two rooms. One room was “The Shells room”, and the other was “The Everything Else room”. We gave a runthrough to some people who’d joined the Shells rooms, and one person asked a pivotal question: shouldn’t shell corporations contain other shell corporations?

With this prompting, we realized Shell 3’s answer could be excellent for Shell 4, and asked across the room if anyone else’s shell wanted Shell 1’s answer. The Shell 2 group said it worked for them, and the entire room perked up. Realizing we should now attempt backsolving metas, we backsolved Shell 7, re-forward solved it to get the answer for Shell 4, and then things got loud as everyone shouted desired constraints and backsolves across the room. While re-forward solving Shell 4, Papa’s Stash got solved, unlocking the blacklight puzzles.

Illegal Search (Sunday)

Jargon (Under Blacklight) - Can’t believe the Lingo people left me to the wolves again!!! Rude. They barged into the Shell room (as the person who had all progress was working on Shells), went straight to our Lingo re-solve, re-solved the puzzle, and then immediately went back to the Everything Else room.

Paper Trail (Sunday, Part 2)

Looking back at Shell 4, we understood the feeder constraints, but not how to forward-solve the puzzle, and moved on to other metas. The rest of our solve path was a backsolve of Shell 6, a side-solve of Shell 2, a forward solve of Shell 8, a partial forward solve of Shell 5 (enough to understand the feeders it used), then a backsolve of Shell 5 before we finished the forward solve to unlock Shell Game.

The Shell Game - The majority of the Shells room was asked to finish forward solving Shell 6 to resolve the graph, while a smaller group of around 8 of us double-checked the shell graph and debated metameta mechanics. I verified that yes, that shell does go to itself, we’d put it in as a “fuck it we ball” placeholder and now that we had 100% info I confirmed it as “yep we do ball”.

The rough idea from the mechanics team was to draw paths using our feeders, but the edge counts didn’t line up the way we wanted (number of unique letters was off in an unhelpful way). To fix this, our team tried writing feeder answer letters out of order, which felt unsatisfying. As Shell 6 got cleaned up (including the “what the fuck” update to our graph), I volunteered to go to the Gala to verify we weren’t totally off track. At this time, it was 5 PM, hints were free-for-all, and we really wanted to make sure we got to do the runaround.

On my way to the Gala, I ran into a huge contingent of Providence solvers in the hallway, and reported that Providence was likely about to finish. I got confirmation that our graph was correct, and that our idea was mostly correct, with a nudge to “consider the entire corporate structure”. This was just big enough for me to get the correct idea, which I messaged ahead as I walked back. When I entered the Shells room, there was only chaos. The Killer had been solved on my walk back, so everyone had migrated to the Shells room. There were 4 working copies of the puzzle (2 on blackboards, 1 in Excalidraw, and another in someone’s solo program), and we decided not to consolidate them, instead treating each as a redundant backup in case others hit a contradiction. I decided I literally would not be able to get close enough to the blackboard to contribute to the graph, and spent my time discussing meta puns instead. Our solve went through a bit after 6 PM, and to celebrate, we mass-unlocked our remaining Stakeout puzzles to chew on while waiting for our endgame interactions. I contributed a bit to Men’s at My Nose, but mostly helped on cleaning up our HQ.

Endgame

As explained in the wrap-up, in the runaround, teams ended up at the Finster vault. The door was locked with an audio lock installed by Sidecar. To open the lock, we needed to do Foley sounds for a 3 minute silent movie. Only one person could see the movie through a hole in the vault door. The room would record audio as the movie played, then it would play back the movie (with recorded audio) on a big projector.

The audio in wrap-up explaining this was a bit muted, so, for your viewing pleasure, here is our first attempt.

Yeah, in retrospect, using audio cues to signal people during sound recording was a bad idea. Others and I recorded this with the plan of referring to the recording for the 2nd attempt, but Death & Mayhem quickly came over and gave an in-universe speech about how it was impossible for us to have such compact video cameras in this day and age, and that we should only look at recordings later. We did it properly the second time. Or more accurately, we spent so long writing down and planning our coordination that Death & Mayhem told us “the lock’s not that sensitive”, so that they could clear the vault for the next runaround. We opened the lock, and finished Hunt.

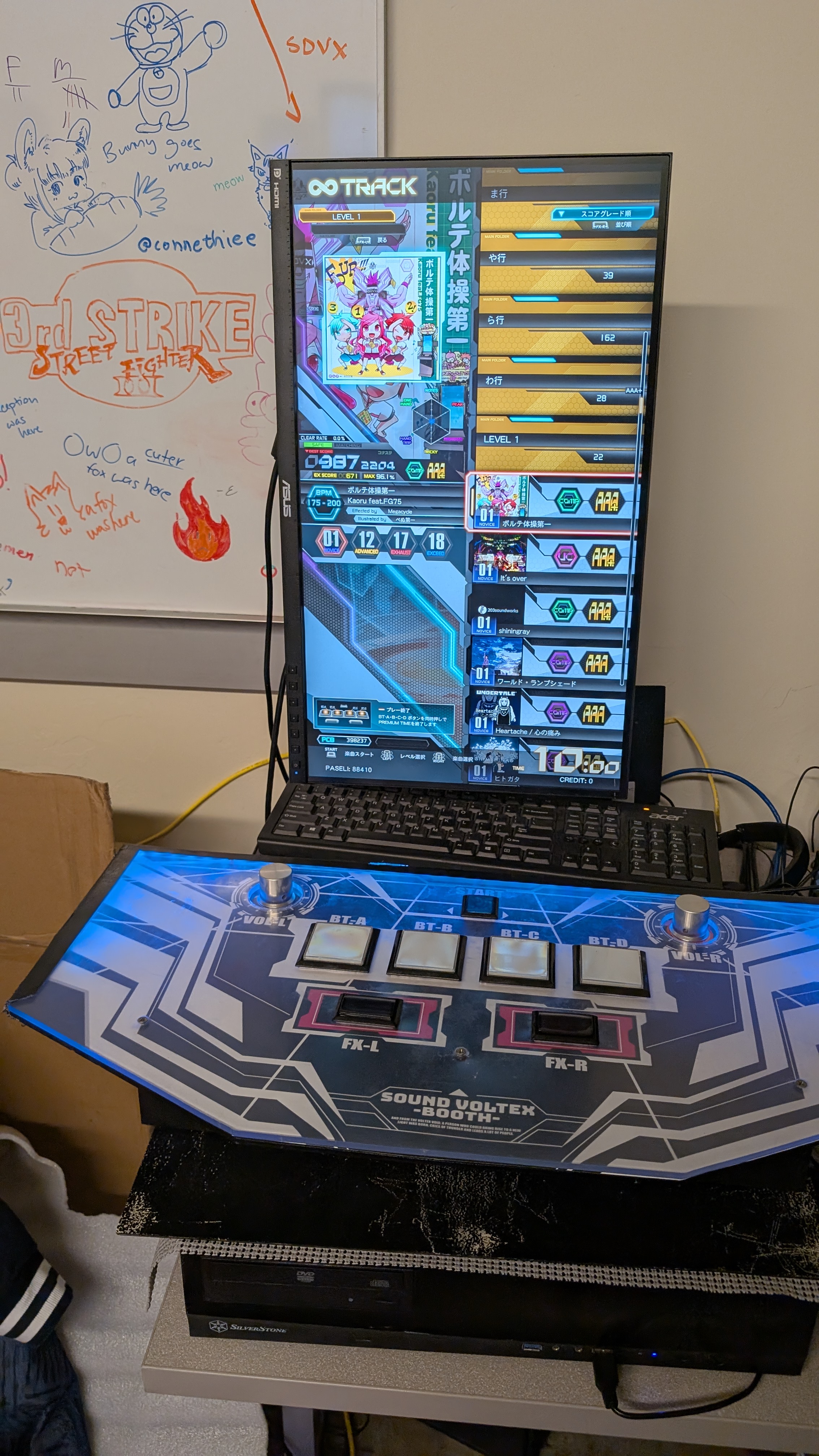

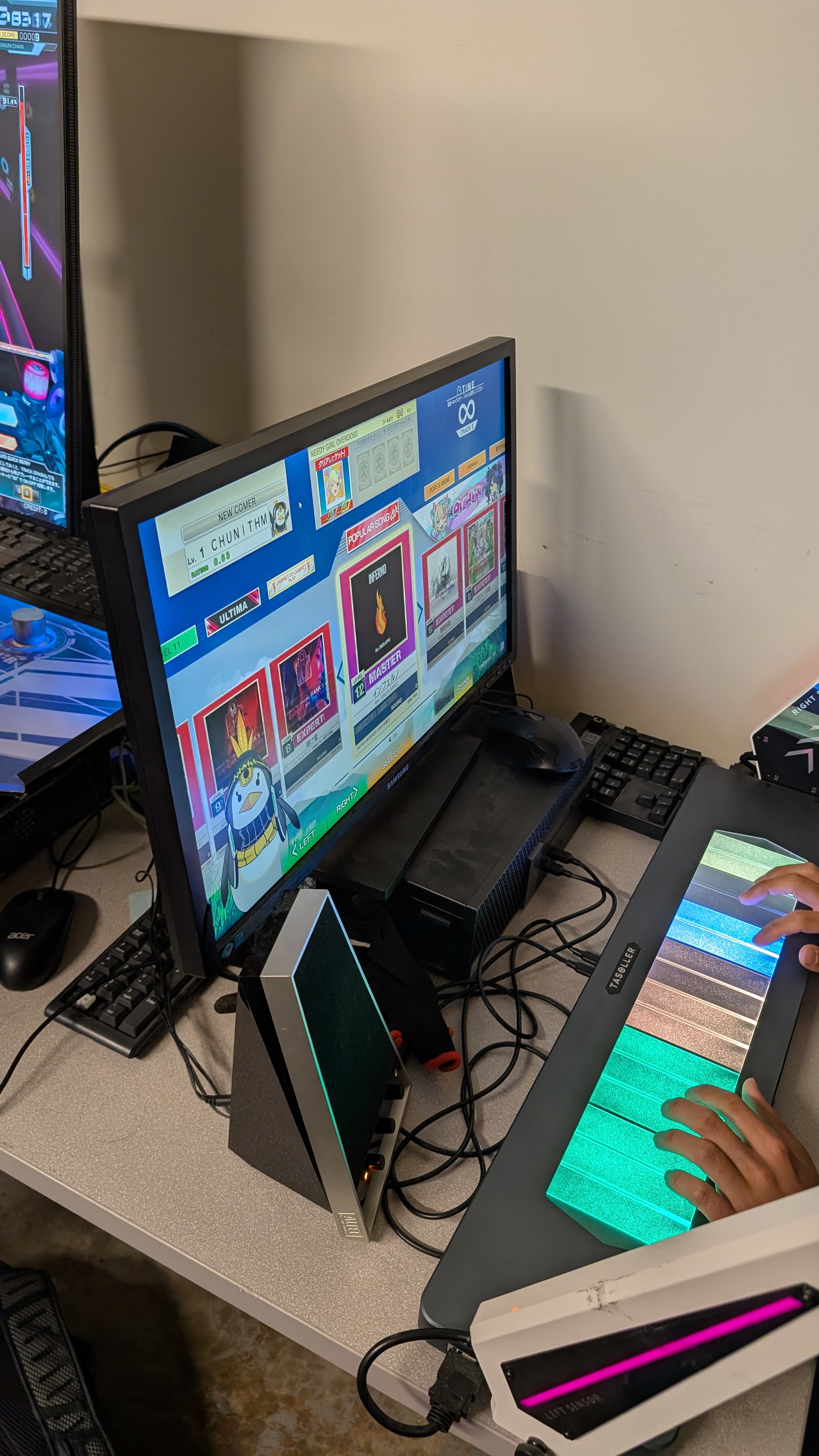

I helped clean up HQ, then walked through the snow with a few others to the MIT rhythm game room to fumble on DDR, get confused about the knobs on Super Voltex, and play exactly 1 song of CHUNITHM.

This post ended up being a lot longer than I expected it to…but that is how all my Mystery Hunt posts go. This is my 10th post about Mystery Hunt, a milestone I find slightly disquieting. I never went to MIT, but after over 10 weekends of attending, there are campus corridors I recognize by heart. I feel privileged that I get to experience this narrow and biased slice of MIT culture every year, and I’m looking forward to seeing people next year.

-

Using AI to Get the Neopets Destruct-o-Match Avatar

CommentsI have blogged about Neopets before, but a quick refresher. Neopets is a web game from the early 2000s, which recently celebrated its 25th anniversary and maintains a small audience of adult millennials. It’s a bit tricky to sum up the appeal of Neopets, but I like the combination of Web 1.0 nostalgia and long-running progression systems. There are many intersecting achievement tracks you can go for, some of which are exceedingly hard to complete. Among them are books, pet training, stamp collecting, gourmet foods, Kadoaties, and more.

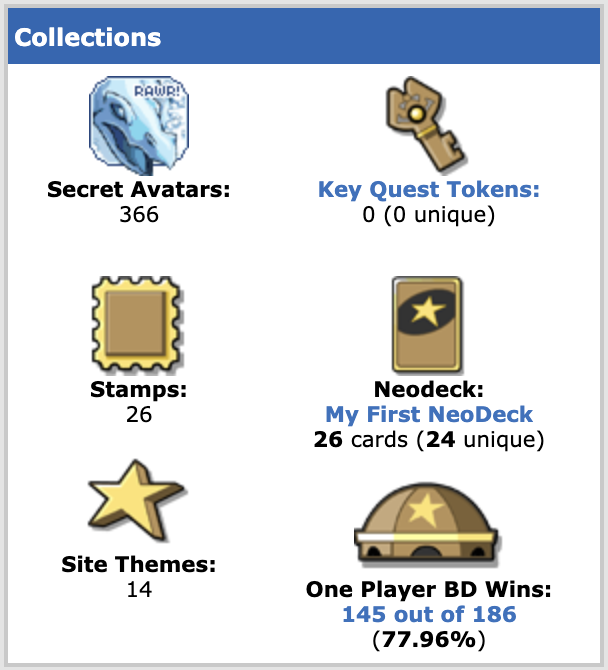

The one I’ve been chasing the past few years is avatars. Neopets has an onsite forum called the Neoboards. This forum is heavily moderated, so you can only use avatars that have been created by TNT. Some are available to everyone, but most have unlock requirements. The number of avatars someone has is a quantification of how much investment they’ve put into Neopets. In my opinion, avatars are the best achievement track to chase, because their unlocks cover the widest cross-section of the site. To get all the avatars, you’ll need to do site events, collect stamps, play games, do dailies, and more. There’s a reason they get listed first in your profile summary!

The avatar I’m using right now literally took me 5 years to unlock. I’m very glad I have it.

Avatars start easy, but can become fiendishly difficult. To give a sense of how far they can go, let me quote the post I wrote on the Neopets economy.

The Hidden Tower Grimoires are books, and unlike the other Hidden Tower items, they’re entirely untradable. You can only buy them from the Hidden Tower, with the most expensive one costing 10,000,000 NP. Each book grants an avatar when read, disappearing on use.

Remember the story of the I Am Rich iOS app, that cost $1000, and did literally nothing? Buying the most expensive Grimoire for the avatar is just pure conspicuous consumption. […] They target the top 1% by creating a new status symbol.

I don’t consider myself the Neopets top 1%, but since writing that post, I’ve bought all 3 Hidden Tower books just to get the avatars…so yeah, they got me.

Avatars can be divided by category, and one big category is Flash games. These avatars all have the same format: “get at least X points in this game.” Most of the game thresholds are evil, since they were set to be a challenge based on high-score tables from the height of Neopets’ popularity. Getting an avatar score usually requires a mix of mastery and luck.

Of these avatars, one I’ve eyed for a long time is Destruct-o-Match.

Destruct-o-Match is a block clearing game that I genuinely find fun. Given a starting board, you can clear any group of 2 or more connected blocks of the same color. Each time you do so, every other block falls according to gravity. Your goal is to clear as many blocks as possible. You earn more points for clearing large groups at once, and having fewer blocks leftover when you run out of moves. The game is made of 10 levels, starting with a 12 x 14 grid of 4 colors and ending with a 16 x 18 grid of 9 colors.

My best score as a kid was 1198 points. The avatar score is 2500. For context, top humans can reach around 2900 to 3000 points on a good run.

Part of the reason this has always been a white whale for me is that it’s almost entirely deterministic from the start state. You could, in theory, figure out the optimal sequence of moves for each level to maximize your score. Actually doing so would take forever, but you could. There’s RNG, but there’s skill too.

Destruct-o-Match can be viewed as a turn based game, where your moves are deciding what boulders to remove. That puts it in the camp of games like Chess and Go, where AI developers have created bots that play at a superhuman level. If AI can be superhuman at Go, surely AI can be slightly-worse-than-experts at Destruct-o-Match if we try?

This is the story of me trying.

Step 0: Is Making a Destruct-o-Match AI Against Neopets Rules?

There’s a gray area for what tools are allowed on Neopets. In general, any bot or browser extension that does game actions or browser requests for you is 100% cheating. Things that are quality-of-life improvements like rearranging the site layout are fine. Anything in-between depends on if it crosses the line from quality-of-life improvement to excessive game assistance, but the line is hard to define.

I believe the precedent is in favor of a Destruct-o-Match AI being okay. Solvers exist for many existing Flash games, such as an anagram solver for Castle of Eliv Thade, Sudoku solvers for Roodoku, and a Mysterious Negg Cave Puzzle Solver for the Negg Cave daily puzzle. These all cross the line from game walkthrough to computer assisted game help, and are all uncontroversial. As long as I’m the one inputting moves the Destruct-o-Match AI recommends, I should be okay.

Step 1: Rules Engine

Like most AI applications, the AI is the easy part, and engineering everything around it is the hard part. To write a game AI, we first need to implement the rules of the game in code. We’ll be implementing the HTML5 version of the game, since it has a few changes from the Flash version that make it much easier to get a high score. The most important one is that you can earn points in Zen Mode, which removes the point thresholds that can cause you to fail levels and Game Over early in the Flash version.

To represent the game, we’ll view it as a Markov decision process (MDP), since that’s the standard formulation people use in the literature. A Markov decision process is made of 4 components:

- The state space, covering all possible states of the game.

- The action space, covering all possible actions from a given state.

- The transition dynamics, describing what next state you’ll reach after doing an action.

- The reward, how much we get for doing that action. We are trying to maximize the total reward over all timesteps.

Translating Destruct-o-Match in these terms,

- The state space is the shape of the grid and the color of each block in that grid.

- The possible actions are the different groups of matching color.

- The transition dynamics are the application of gravity after a group is removed.

- The reward is the number of points the removed group is worth, and the end score bonus if we’ve run out of moves.

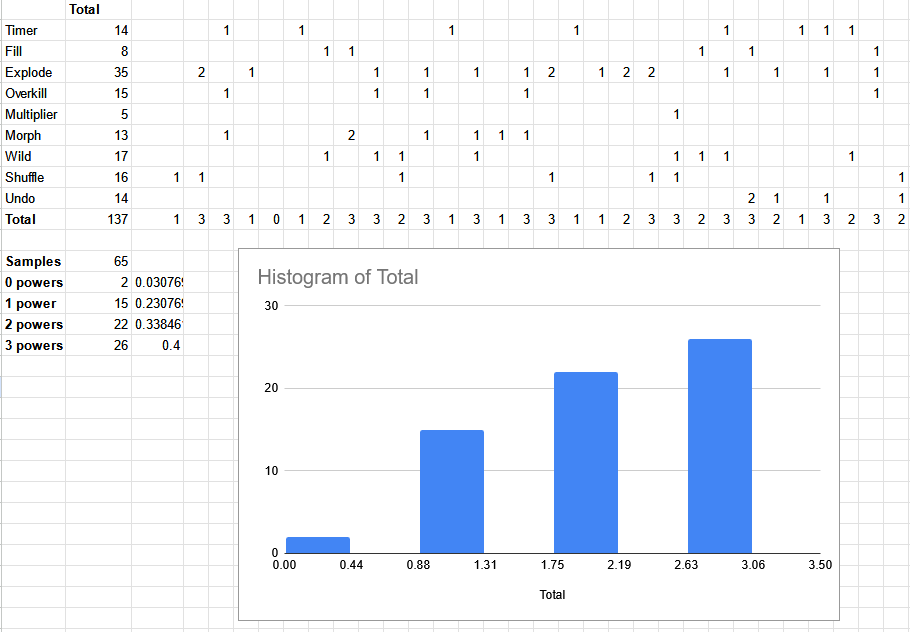

The reward is the easiest to implement, following this scoring table.

Boulders Cleared Points per Boulder Bonus Points 2-4 1 - 5-6 1 1 7 1 2 8-9 1 3 10 1 4 11 1 6 12-13 1 7 14 1 8 15 1 9 16+ 2 - The end level bonus is 100 points, minus 10 points for every leftover boulder.

Boulders Remaining Bonus Points 0 100 1 90 2 80 3 70 4 60 5 50 6 40 7 30 8 20 9 10 10+ 0 Gravity is also not too hard to implement. The most complicated and expensive logic is on identifying the possible actions. We can repeatedly apply the flood-fill algorithm to find groups of the same color, continuing until all boulders are assigned to some group. The actions are then the set of groups with at least 2 boulders. This runs in time proportional to the size of the board. However, it’s not quite that simple, thanks to one important part of Destruct-o-Match: powerups.

Powerups

Powerups are very important to scoring in Destruct-o-Match, so we need to model them accurately. Going through them in order:

The Timer Boulder counts down from 15 seconds, and becomes unclearable if not removed before then.

The Fill Boulder will add an extra line of blocks on top when cleared.

The Explode Boulder is its own color and is always a valid move. When clicked, it and all adjacent boulders (including diagonals) are removed, scoring no points.

The Overkill Boulder destroys all boulders of matching color when cleared, but you only get points for the group containing the Overkill.

The Multiplier Boulder multiples the score of the group it's in by 3x.

The Morph Boulder cycles between boulder colors every few seconds.

The Wild Boulder matches any color, meaning it can be part of multiple valid moves.

The Shuffle Boulder gives a one-shot use of shuffling boulder colors randomly. The grid shape will stay fixed. You can bank 1 shuffle use at a time, and it carries across levels.

The Undo Boulder gives a one-shot use of undoing your last move, as long as it did not involve a power-up. Similar to shuffles, you can bank 1 use at a time and it carries across levels. In the HTML5 version, you keep all points from the undone move. We can keep the game simpler by ignoring the Shuffle and Undo powerups. These both assist in earning points, but they introduce problems. Shuffle would require implementing randomness. This would be harder for the AI to handle, because we’d have to average over the many possible future states to estimate the value of each action. It’s possible, just expensive. Meanwhile, Undos require carrying around history in the state, which I just don’t want to deal with. So, I’ll have my rules engine pretend these powerups don’t exist. This will give up some points, but remember, we’re not targeting perfect play. We just want “good enough” play to hit the avatar score of 2500. Introducing slack is okay if we make up for it later. (I can always use the Shuffle or Undo myself if I spot a good opportunity to do so later.)

Along similar lines, I will ignore the Fill powerup because it adds randomness on what blocks get added, and will ignore the Timer powerup because I want to treat the game as a turn-based game. These are harder to ignore. My plan is to commit to clearing Timer boulders and Fill boulders as soon as I start the level. Then I’ll transcribe the resulting grid into the AI and let it take over from there.

This leaves Explode, Overkill, Multiplier, Morph, and Wild. Morph can be treated as identical to Wild, since we can wait for the Morph boulder to become whatever color we want it to be. The complexity these powers add is that after identifying a connected group, we may remove boulders outside that group. A group of blue boulders with an Overkill needs to remove every other blue boulder. So, for every group identified via flood-fill, we note any powerups contained in that group, then iterate over them to define an “also-removed” set for that action. (There are a lot of minor, uninteresting details here, my favorite of which was that Wild Boulders are not the same color as Explode Boulders and Explode Boulders are not the same color as themselves.) But with those details handled, we’re done with the rules engine!

Well, almost done.

Step 2: Initial State

Although I tried to remove all randomness, one source of randomness I can’t ignore is how powerups are initially distributed.

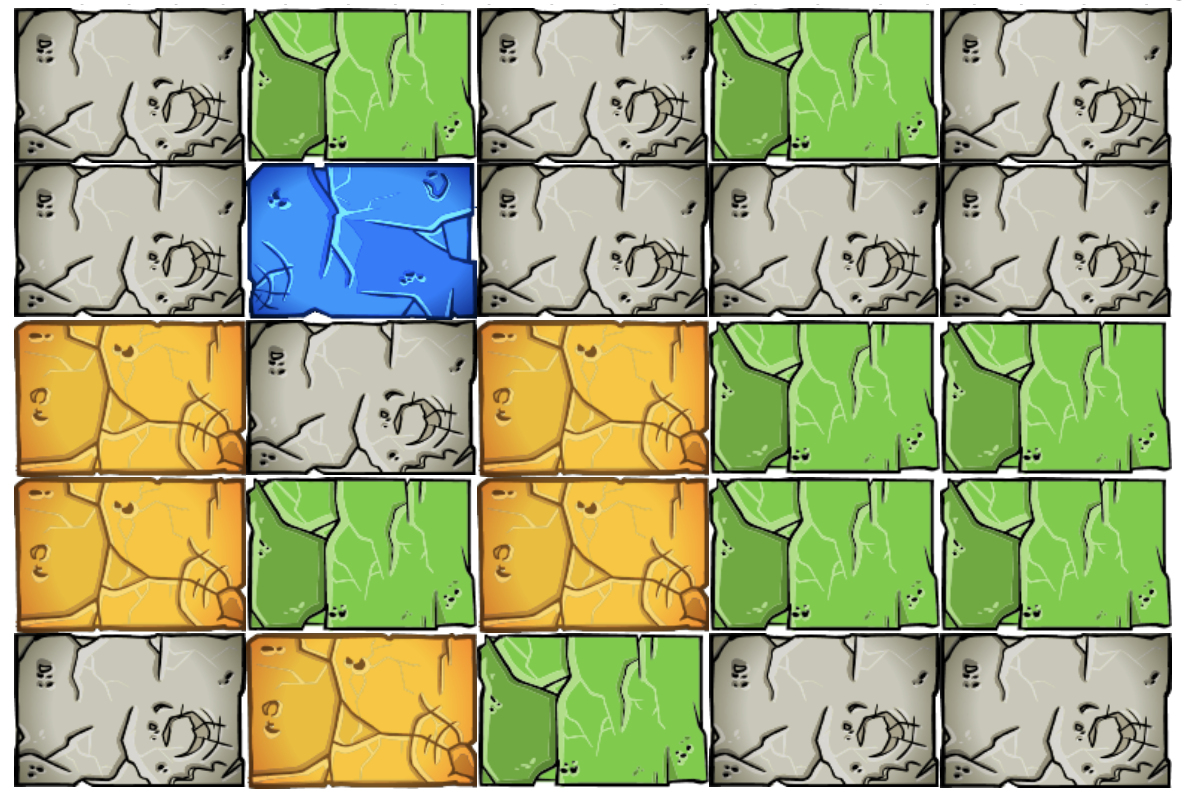

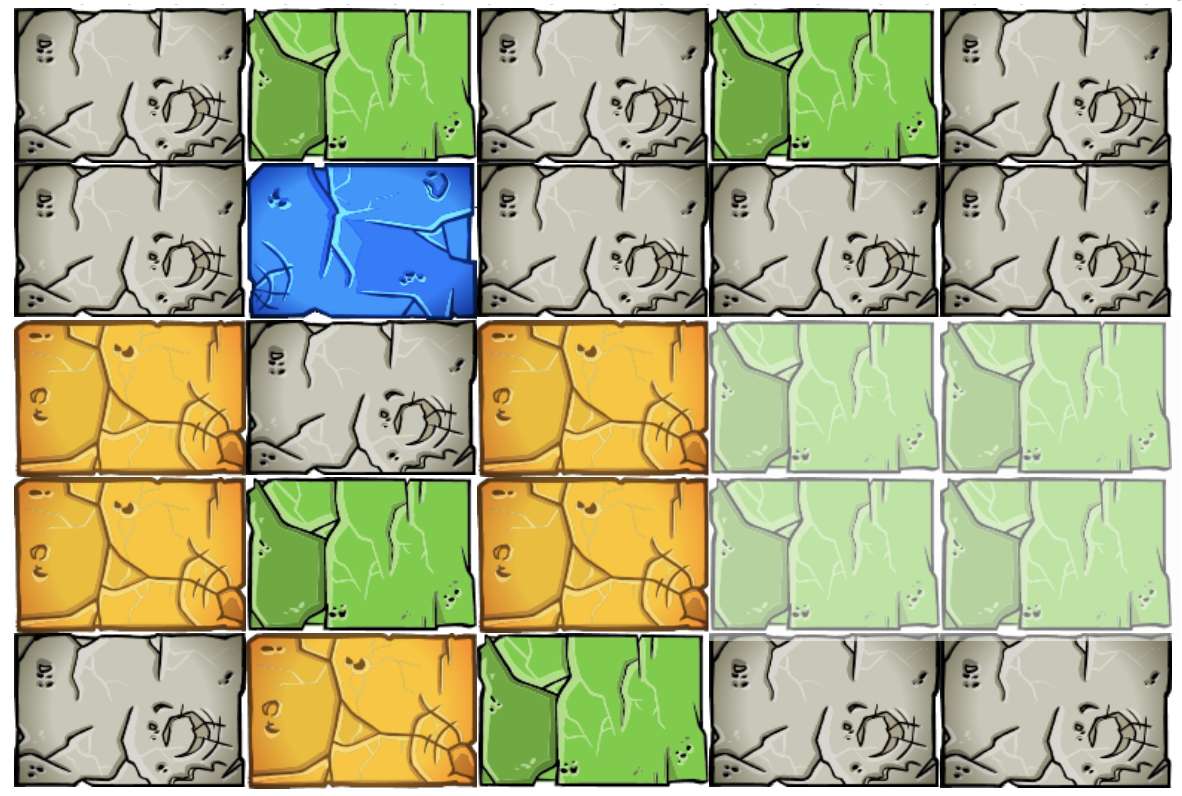

Of the powerups, the Multiplier Boulder is clearly very valuable. Multiplying score by 3x can be worth a lot, and avatar runs are often decided by how many Multipliers you see that run. So for my AI to be useful, I need to know how often each powerup appears.

I couldn’t find any information about this on the fan sites, so I did what any reasonable person would do and created a spreadsheet to figure it out for myself.

I played 65 levels of Destruct-o-Match, tracking data for each one. Based on this data, I believe Destruct-o-Match first randomly picks a number from 0-3 for how many powerups will be on the board. If powerups were randomly selected per block, I would have seen more than 3 powerups at some point. I observed 0 powerups 3% of the time, 1 powerup 23% of the time, 2 powerups 34% of the time, and 3 powerups 40% of the time. For reverse engineering, I’m applying “programmer’s bias” - someone made this game, and it’s more likely they picked round, nice numbers. I decided to round to multiples of 5, giving 0 = 5%, 1 = 20%, 2 = 35%, 3 = 40% for powerup counts.

Looking at the powerup frequency, Explode clearly appears the most and Multiplier appears the least. Again applying some nice number bias, I assume that Explodes are 2x more likely than a typical powerup, Fills are 2/3rd as likely, and Multipliers are 1/3rd as likely, since this matches the data pretty well.

An aside here: in testing on the Flash version, I’ve seen more than 3 powerups appear, so the algorithm used there differs in some way.

Step 3: Sanity Check

Before going any further down the rabbit hole, let’s check how much impact skill has on Destruct-o-Match scores. If the scores are mostly driven by RNG, I should go play more games instead of developing the AI.

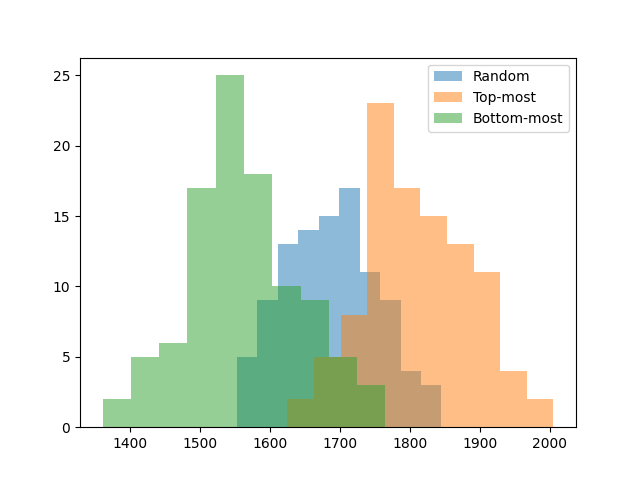

I implemented 3 basic strategies:

- Random: Removes a random group.

- Top-Down: Removes the top-most group.

- Bottom-Up: Removes the bottom-most group.

Random is a simple baseline that maps to a human player spamming clicks without thinking. (I have done this many, many times when I just want a game to be over.) Top-down and bottom-up are two suggested strategies from the JellyNeo fan page. Top-down won’t mess up existing groups but makes it harder to create new groups, since fewer blocks change location when falling. Bottom-up can create groups by causing more blocks to fall, but it can also break apart existing larger groups, which hurts bonus points.

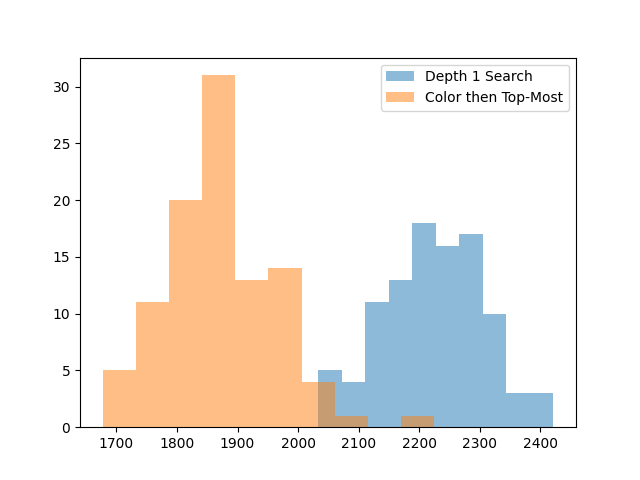

For each strategy, I simulated 100 random games and plotted the distribution of scores.

The good news is that strategy makes a significant difference. Even a simple top-most strategy is 100 points better than random. This also lets us know that the bottom-up strategy sucks. Which makes sense: bottom-up strategies introduce chaos, it’s hard to make large groups of the same color in chaos, and we want large groups for the bonus points. For human play, this suggests it’s better to remove groups near the top unless we have a reason not to.

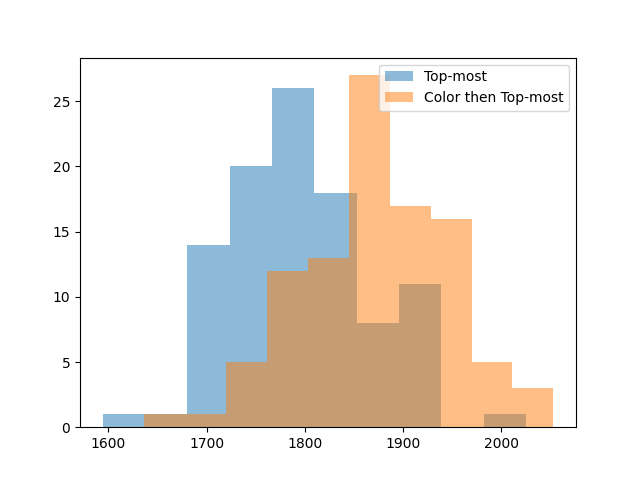

One last recommended human strategy is to remove blocks in order of color. The idea is that if you leave fewer colors on the board, the remaining groups will connect into large groups more often, giving you more bonus points. We can try this strategy too, removing groups in color order, tiebreaking with the top-down heuristic that did well earlier.

Removing in color order gives another 100 points on average. We can try one more idea: if bottom-up is bad because it breaks apart large groups, maybe it’d be good to remove large groups first, to lock in our gains. Let’s remove groups first in order of color, then in order of size, then in order of which is on top.

This doesn’t seem to improve things, so let’s not use it.

These baselines are all quite far from the avatar score of 2500. Even the luckiest game out of 100 attempts only gets to 2100 points. It is now (finally) time to implement the AI.

Step 4: The AI

To truly max the AI’s score, it would be best to follow the example of AlphaZero or MuZero. Those methods work by running a very large number of simulated games with MCTS, training a neural net to predict the value of boards from billions of games of data, and using that neural net to train itself with billions more games.

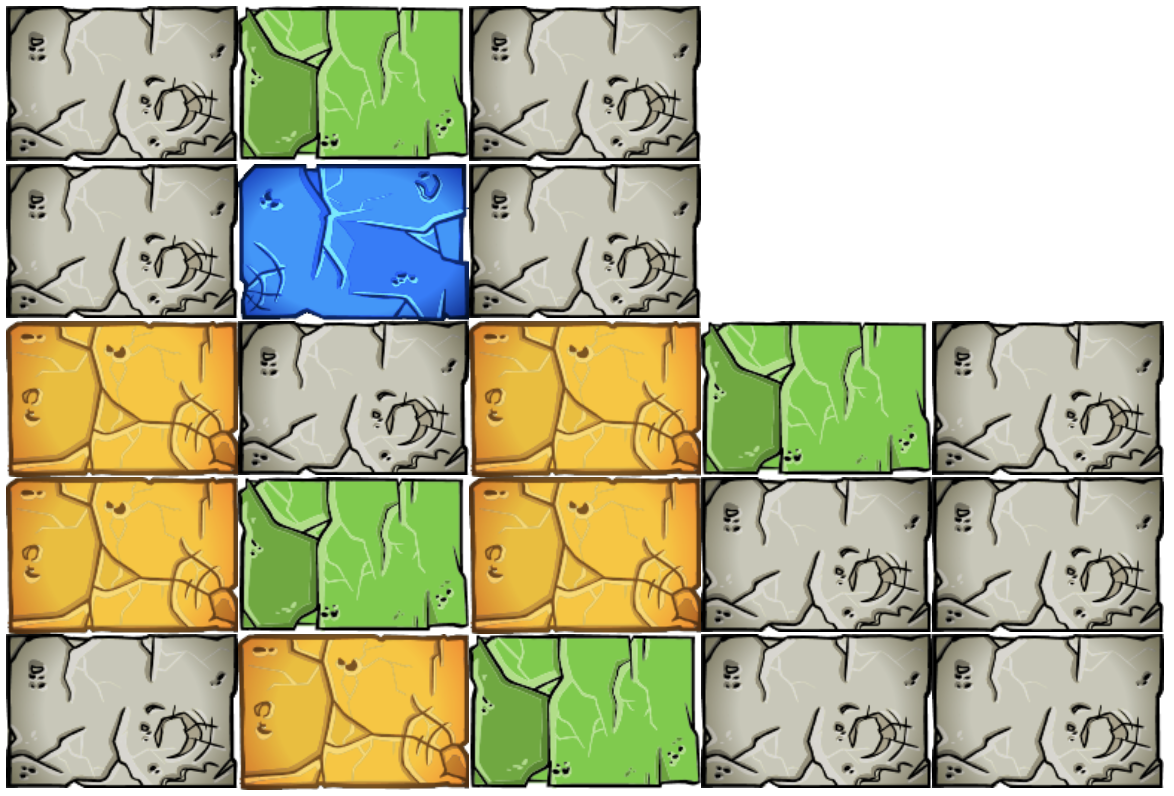

I don’t want to invest that much compute or time, so instead we’re going to use something closer to the first chess AIs: search with a handcoded value function. The value of a state \(s\) is usually denoted as \(V(s)\), and is the estimated total reward if we play the game to completion starting from state \(s\). If we have a value function \(V(s)\), then we can find the best action by computing what’s known as the Q-value. The Q-value \(Q(s,a)\) is the total reward we’ll achieve if we start in state \(s\) and perform action \(a\), and can be defined as.

\[Q(s,a) = reward(a) + Value(\text{next state}) = r + V(s')\]Here \(s'\) is the common notation for “next state”. The action \(a\) with largest Q-value is the action the AI believes is best.

So how do we estimate the value? We can conservatively estimate a board’s value as the sum of points we’d get from every group that exists within it, plus the end-level bonus for every boulder that isn’t in one of those groups. This corresponds to scoring every existing group and assuming no new groups will be formed if all existing groups are removed. Doing so should be possible on most boards, if we order the groups such that a group is removed only after every group above it has been removed. Unfortunately, there are some edge cases where it isn’t possible, such as this double-C example, where groups depend on each other in a cycle.

In this example, we cannot earn full points for both the blue group and green group, because removing either will break apart the other.

We could determine if it’s possible to score every group by running a topological sort algorithm, but for our purposes we only need the value function to be an approximation, and we want the value function to be fast. So, I decided to just ignore these edge cases, for the sake of speed.

We can reuse the logic we used to find every possible action to find all groups in the grid. This gives a value estimate of

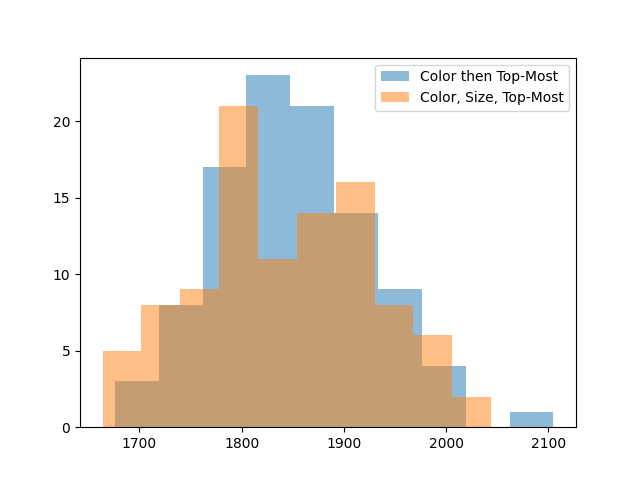

\[V(s) = \sum_{a} reward(a)\]Here is our new method for choosing actions.

- From the current state \(s\), compute every possible action \(a\).

- For each action \(a\), find the next state \(s'\) then compute Q-value \(Q(s,a) = r + V(s')\).

- Pick the action with best Q-value.

- Break ties with the color then top-most heuristic that did best earlier.

Even though this only looks 1 move ahead, it’s quite effective. By a lot.

This is enough to give a 400 point boost on its own. This gain was big enough that I decided to try playing a game with this AI, and I actually got pretty close to winning on my first try, with 2433 points.

The reason I got so many points compared to the distribution above is a combination of using Shuffles for points and beneficial bugs. I don’t know how, but I got a lot more points from the end-level bonuses in levels 3 and 4 than I was supposed to. I noticed that levels 3 and 4 are only 12 x 15 instead of 13 x 15 from the Flash version, so there may be some other bug going on there.

Still, this is a good sign! We only need to crank out 70 more points. If we can get this close only looking 1 move ahead, let’s plan further out.

Step 5: Just Go Harder

Early, we defined the Q-value as

\[Q(s,a) = reward(a) + Value(\text{next state})\]This is sometimes called the 1-step Q-value, because we check the value after doing 1 timestep. We can generalize this to the n-step Q-value by defining it as

\[Q(s,a_1,a_2,\cdots,a_n) = r_1 + r_2 + \cdots + r_n + Value(\text{state after n moves})\]Here each reward \(r_i\) is the points we get from doing action \(a_i\). We take the max over all sequences of \(n\) actions, run the 1st action in the best sequence, then repeat.

One natural question to ask here is, if we’ve found the best sequence of \(n\) moves, why are we only acting according to the 1st move in that sequence? Why not run all \(n\) actions from that sequence? The reason is because our value estimate is only an approximation of the true value. The sequence we found may be the best one according to that approximation, but that doesn’t make it the actual best sequence. By replanning every action, the AI can be more reactive to the true rewards it gets from the game.

This is all fine theoretically, but unfortunately an exhaustive search of 2 moves ahead is already a bit slow in my engine. This is what I get for prioritizing ease of implementation over speed, and doing everything in single-threaded Python. It is not entirely my fault though. Destruct-o-Match is genuinely a rough game for exhaustive search. The branching factor \(b\) of a game is the number of valid moves available per state. A depth \(d\) search will require considering \(b^d\) sequences of actions, exponential in the branching factor, so \(b\) is often considered a proxy for search difficulty.

To set a baseline, the branching factor of Chess averages 31 to 35 legal moves. In my analysis, the start board in Destruct-o-Match has an average of 34 legal moves. Destruct-o-Match is as expensive to search as Chess. This is actually so crazy to me, and makes me feel less bad about working on this. If people can dedicate their life to Chess, I can dedicate two weeks to a Destruct-o-Match side project.

To handle this branching factor, we can use search tree pruning. Instead of considering every possible action, at each timestep, we should consider only the \(k\) most promising actions. This could miss some potentially high reward sequences if they start with low scoring moves, but it makes it more practical to search deeper over longer sequences. This is often a worthwhile trade-off.

Quick aside: in college, I once went to a coding competition where we split into groups, and had to code the best Ntris bot in 4 hours. I handled game logic, while a teammate handled the search. Their pruned search tree algorithm destroyed everyone, winning us $500 in gift cards. It worked well then, so I was pretty confident it would work here too.

Here’s the new algorithm, assuming we prune all but the top \(k\) actions.

- From the current state, compute every possible action.

- For each action, find the next state \(s'\) and the 1-step Q-value \(Q(s,a)\).

- Sort the Q-values and discard all but the top \(k\) actions \(a_1, a_2, \cdots, a_k\).

- For each next state \(s'\), repeat steps 1-3, again only considering the best \(k\) actions from that \(s'\). When estimating Q-value, use the n-step Q-value, for the sequence of actions needed to reach the state we’re currently considering.

- By the end, we’ll have computed a ton of n-step Q-values. After hitting the max depth \(d\), stop and return the first action of the sequence with best Q-value.

If we prune to \(k\) actions in every step, this ends up costing \(b\cdot k^d\) time. There are \(k^d\) different nodes in the search tree and we need to consider the Q-values of all \(b\) actions from each node in that tree to find the best \(k\) actions for the next iteration. The main choices now are how to set \(k\) and max depth \(d\).

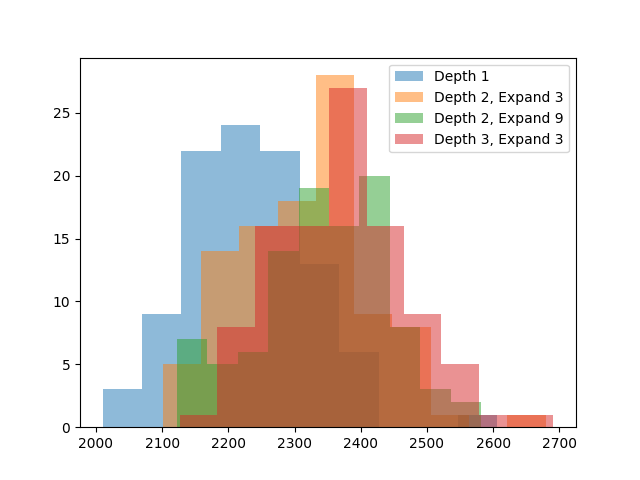

To understand the trade-off better, I did 3 runs. One with

Depth=2, Expand=3, one withDepth=2, Expand=9, and one withDepth=3, Expand=3. The first is to verify there are gains from increasing search depth at all. The second two are 2 compute-equivalent configurations, one searching wider and the other searching deeper.

The gains are getting harder to spot, so here are more exact averages.

Depth 1: 2233.38

Depth 2, Expand 3: 2318.32

Depth 2, Expand 9: 2343.34

Depth 3, Expand 3: 2373.37Searching deeper does help, it is better than searching wider, and the

Depth 3, Expand 3configuration is 140 points better than the original depth 1 search. This should be enough for an avatar score. This search is also near the limit of what I can reasonably evaluate. Due to its exponential nature, it’s very easy for search to become expensive to run. The plot above took 7 hours to simulate.For the final real game, I decided to use

Depth 3, Expand 6. There’s no eval numbers for this, but increasing the number of considered moves can only help. In local testing, Depth 3 Expand 6 took 1.5 seconds on average to pick an action on my laptop, which was just long enough to feel annoying, but short enough to not be that annoying.After starting up the AI, I played a Destruct-o-Match game over the course of 3 hours. By my estimate, the AI was only processing for 15 minutes, and the remaining 2 hr 45 min was me manually transcribing boards into the AI and executing the moves it recommended. The final result?

An avatar score! Hooray! If I had planned ahead more, I would have saved the game state sequence to show a replay of the winning game, but I didn’t realize this until later, and I have no interest in playing another 3 hour Destruct-o-Match game.

Outtakes and Final Thoughts

You may have noticed I spent almost all my time transcribing the board for the AI. My original plan was to use computer vision to auto-convert a screenshot of the webpage into the game state. I know this is possible, but unfortunately I messed something up in my pattern-matching logic and failed to debug it. I eventually decided that fixing it would take more time than entering boards by hand, given that I was only planning to play the game 1-2 times.

After I got the avatar, I ran a full evaluation of the

Depth 3, Expand 6configuration overnight. It averages 2426.84 points, another 53 points over theDepth 3, Expand 3setting evaluated earlier. Based on this, you could definitely squeeze more juice out of search if you were willing to wait longer.Some final commentary, based on studying games played by the AI:

- Search gains many points via near-perfect clears on early levels. The AI frequently clears the first few levels with 0-3 blocks left, which adds up to a 200-300 point bonus relative to baselines that fail to perfect clear. However, it starts failing to get clear bonuses by around level 6. Based on this, I suspect Fill powerups are mostly bad until late game. Although Fills give you more material to score points with, it’s not worth it if you end with even a single extra leftover boulder that costs you 10 points later. It is only worth it once you expect to end levels with > 10 blocks left.

- The AI jumps all over the board, constantly switching between colors and groups near the top or bottom. This suggests there are a lot of intentional moves you can make to get boulders of the same color grouped together, if you’re willing to calculate it.

- The AI consistently assembles groups of 16+ boulders in the early levels. This makes early undos very strong, since they are easily worth 32-40 points each. My winning run was partly from a Multiplier in level 1, but was really carried by getting two Undos in level 2.

- Whoever designed the Flash game was a monster. In the original Flash game, you only get to proceed to the next level if you earn enough points within the current level, with the point thresholds increasing the further you get. But the AI actually earns fewer points per level as the game progresses. My AI averages 203 points in level 7 and 185 points in level 9. If the point thresholds were enforced in the HTML5 version, the AI would regularly fail by level 7 or 8.

I do wonder if I could have gotten the avatar faster by practicing Destruct-o-Match myself, instead of doing all this work. The answer is probably yes, but getting the avatar this way was definitely more fun.